The Mahabharata is often known as the fifth Veda. It has often been said that reading the Mahabharata from start to finish will fill the reader’s mind with such knowledge and enlightenment that he is sure to achieve heaven. Whether or not that is true, the epic is a virtual forest of stories, with new ones taking root every second. Here is a list of five stories that are not that often repeated.

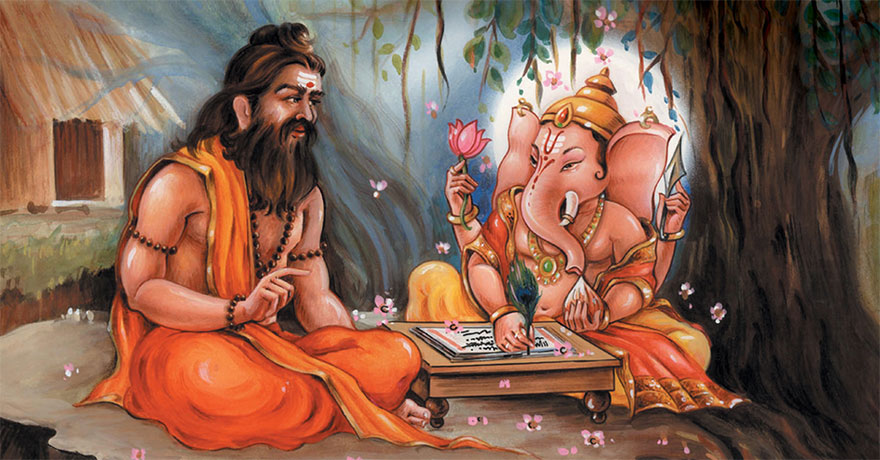

1. Sage and Scribe

The Mahabharata is said to have been written down by Lord Ganesha, to the dictation of Vyasa. At the beginning of the exercise, Ganesha says to Vyasa, ‘Lord, I shall write for you on one condition; that you recite the verses at such a speed that my pen shall never stop.’ To that Vyasa said, ‘So be it, my lord. In that case my condition is that you shall only write down a verse after you have understood its meaning.’

With this understanding they sat down, and every time Vyasa wanted a break from his recital he would throw in a difficult verse or two for Ganesha to ponder upon, and while the elephant-god thought, the sage rested. Some say that sage and scribe are still at work in some unseen corner in some unknown forest.

2. Pandu’s Last Wish

When Pandu, the father of the Pandavas, was about to die, he wished for his sons to partake of his brain so that they inherit his wisdom and knowledge. Only Sahadeva paid heed, though; it is said that with the first bite of his father’s brain, he gained knowledge of all that had happened in the universe. With the second he gained knowledge of the present happenings, and with the third he came to know of all that would occur in the future.

Sahadeva, often relegated to silence in the story along with his brother Nakul, is known for his prescience. He is said to have known all along that a great war would come to cleanse the land, but he did not announce it lest that would bring it about. As it happened, staying silent about it did not help either.

An interesting parallel here with Cassandra, princess of Troy, who had the gift of foresight but also the curse that no one would ever believe her. In contrast to Sehdev, Cassandra chose to rave and rant, and was often derided by her own family as a mad woman.

3. Yudhishtir’s chariot

Yudhishtir’s chariot is said to always float three finger-breadths over the ground due to his pious and righteous nature. Until, that is, he tells a half-lie in the war that Ashwatthama, the elephant, has died. Though not technically a lie, it was a bending of the truth designed to force Dronacharya to renounce his arms, and it was enough of a sin for Mother Nature to pull Yudhishtir’s chariot to the ground with a gentle thud.

And Yudhisthir became one of us.

4. The final journey

The five brothers and their wife reach the base of the mountain Sumeru, at the top of which live the Gods. Over the course of the journey, everyone except Yudhishtir falls to their death. For each death, Yudhishtir gives a reason: for Draupadi, it was because she was partial to Arjun in her love; for Arjun, Nakul and Sehdev, it was vanity, whether in prowess, looks or wisdom. For Bhim it was gluttony that finally took his life.

After each death Yudhishtir, usually prone to grief, moves on detachedly, without so much as a backward glance. In this final tale, the Mahabharat suggests that our last walks, when they come, will be the loneliest of all, and only by detaching ourselves from the earthly can we truly achieve lasting peace.

5. Parashurama kills the Kshatriyas

We’ve often spoke of Karna as a character with a deep identity crisis. Prashurama is another that fits the bill. Though a Brahmin by birth and raising, he has a love for weapons and fighting. He’s given to anger and revenge. In an age when Brahmins were meant to be detached, he found himself bound by the Kshatriya bonds of loyalty, prestige and love. So when he hoists his axe onto his shoulder and sets out to cleanse the Earth of Kshatriyas – to exact vengeance for the murder of his parents by Kartaveerya Arjuna, a Kshatriya king – one gets the feeling that he has raised his arms against his own brothers.

Twenty one times he decimates the Kshatriya race, but each time they come back. This is because the line of the Kshatriyas was measured by the line of the women – which is why Kunti’s sons, even though not sired by Pandu, came to be known as Pandu’s sons.

So if Parashurama really wanted to annihilate the Kshatriyas, he would have done well to kill all the women instead. But he didn’t, perhaps deterred by the precept – a Kshatriya precept – that women should not be fought against in battle.

Source: sharathkomarraju.com

I think the author, although has done a good job elsewhere, has erred wrt Parashuram! He did not have identity crisis! How can Vishnu’s avatar have that? He punished the adharmi Kshatriya clans leaving the ones engaged in pious works!!

ABC of life is always be careful avoid bad company

Though some of these tales were told to us in our childhood, they had faded in memory, so it was fun re-reading them. Thanks for the revision. Moreover they can be narrated to children

Rajiv Gogate

Lokaa! Samasthaa! Sughino Bhavanthu!

Mahabharat was,is and will be the greatest ever Historical Epic.Every anyone reading will be seeing a different perception of the esoteric and underlying meanings in each and every single verse.If Lord Ganesha himself had to ponder how much should we be doing. HariOm