Background Information:

These stories are biographical narrations by the author, written down around 20 years ago. This was originally meant to be published as a book, but after completing the first eight chapters, the author chose not to continue, and thus we are left with the stories in their present incomplete form. Most of these stories took place around 1970. The areas discussed in these stories have changed greatly in the last 40 years and may not match what we see today. All of these stories are factual. There is no plan to ever publish this book, so if you want to know more, or if you want to know about other events that occurred, you would have to meet the author personally.

Chapter Five

“If you want to become a high priest of humbug, fine – but you are surely not going to do it on company time!”

The chief accountant, SVS, a spartan, no-nonsense company functionary with a schoolmaster’s mien and sense of metaphor, was addressing me with volume control turned up for the benefit of everyone else in the office. He’d had it up to the eyes; it was time to put his foot down.

I continued sketching my picture of Dattatreya as if I hadn’t heard him. He swept the room with a penetrating You’re Next glare that put noses to the grindstone at desks where a moment before sniggering rubbernecks had sat. Then, after a last withering look at me, he scowled in disgust and grumbled: “You’ll end up painting that picture on the sidewalk for tossed coins, you – you poppycock dreamer!” He stalked off.

It hadn’t been the first time that I’d drawn Dattatreya on valuable company letterhead at my desk. On other occasions I had wasted valuable company time by rambling on endlessly about the difference between the Pashupata and Shaiva Siddhanta sects, or the distinctive features of the Seven Shaktis, or the story of the green huntress Valli and Karttikeya. All this SVS had overlooked because I’d been his star assistant for over two years and had always compensated for my eccentricities with hard work.

But the day before yesterday I’d left work early, without telling anyone. Yesterday I hadn’t come to work at all, and gave no reason. Today I was at my desk, but only drawing pictures of Dattatreya and speaking to no one.

A few minutes later Vaidyanathan put his hand on my shoulder. “Chum, the M.D. (Managing Director) is asking for you. SVS has seen him and raised hell.” Wordlessly, I dropped my pencil, stood up, and ambled into the the M.D.’s office.

He greeted me with a polite smile and invited me to sit down and explain my behavior over the last three days. After a few moment of dead silence while I extracted words from the ether and arranged them in my head, I began.

“The day before yesterday I was called from work to the Dattatreya temple in Chendamangalam…” He put up his hand to interrupt.

“Who called you?”

“Sri Svayamprakash Brahmendra Saraswati, the mahanta of the temple.”

“Accha. So guruji telephoned you here at the office.”

“No. He calls me through the mind.”

“Yes, quite. Kindly continue.”

“I stayed all night at the temple, because a special abhisheka (bathing ceremony) was held at midnight.” Again he interrupted.

“So guruji was having a special festival and invited you through the mind to come.”

“Yes, but he was not there visibly, because he left the world in 1948.”

“Yes, yes. Please go on.”

Lord Dattatreya

“Then, in the early morning hours I left the temple. I came down the hill onto the road. There I met two ghosts. I chanted a Karttikeya mantra and delivered them to the control of Shreshtaraja. The rest of the day I had to take rest. Today I am only thinking of Dattatreya.”

“Only?”

“Yes.”

He gave me that side-to-side nod of the head peculiar to Indians and leaned forward as if to take me in confidence.

After hearing my own voice relate these events, I understood for the first time that I might be losing my mind. I braced myself for what the M.D. was about to say.

He held up a palm and slightly patted the air above his desk while he spoke, as if my poor head was under it.

“Kannan, listen. Things have changed in India. The time of all the gods and temples is gone. Oh, simple folk may carry on with these quaint forms of Hindu piety, but you are an educated young man. You’ve got to keep your eyes on tomorrow, not yesterday.”

I tried speaking up for myself, humbly, knowing full well he was just indulging me with his gentle speech and understanding manner. Of course he thought me mad. I was beginning to think so myself.

“But sir,” I choked, next to tears, “I sincerely believe in the Hindu religion. After investigating tantra, Shakta, Advaita and the other paths, I have come to realize its true value and …”

He patted the air, nodding his head patiently from side to side until my voice trailed off.

“That’s all right, Kannan. I’m not saying you should give up religion. You’ve just got to be realistic about it, that’s all.”

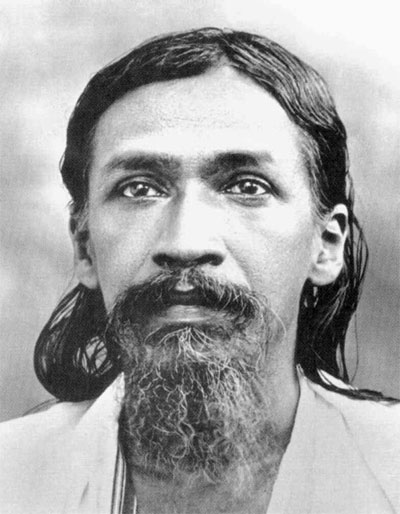

He opened a drawer and very reverently took out two photographs, laying them on his desk for me to see. One was of a sadhu dressed in white, with long hair and beard. The other was of a smiling woman, perhaps a Western lady, I thought.

“This” – he pointed to the sadhu’s picture – “is the avatara of the age. In him all the gods reside. His name is Sri Aurobindo. And this is his shakti, whom we revere as the Mother. Though both have passed on into the realm beyond, they are still very much with us in spirit. Their teachings blend all that you’ve come to value in Hinduism into one scientific synthesis.”

This wasn’t quite what I had expected from the M.D. His eyes were positively alight with glory. All my worries of losing my mind and my job faded, for I was sure if SVS saw the M.D. now, he’d think him a far worse high priest of humbug than I. We were kindred spirits, me and old Directorji, poppycock dreamers duluxe, but somehow he’d made it into the upper echelon of TVS management. So there must be something to say about this Aurobindo thing he was raving on about.

“I will now give you a mantra, Kannan,” he solemnly declared. “I want you to keep these pictures on your desk and offer everything you do to Sri Aurobindo and the Holy Mother. This will bring you back to reality, and you’ll attain the goal of all religions.”

I became a zealous convert. Before touching the pencil in the morning, I would do puja to it, offering incense, a flower and prayers. After writing out a bill, I’d hold it up to the photos, chant the mantra and drop it, sanctified, into the ‘out’ tray. I offered the entries I made in the ledger. And the coffee during the coffee break.

This shifted my mind into the psychic ‘tube’, and right there at work the visions started flowing in. I’d buttonhole someone almost every day, in the office or in the factory, and fill his ears with my latest revelations. If he listened long enough, I’d get a resonance going with his mind, like getting a gong to vibrate by striking another gong of the same pitch. I could then tap into his subconscious and receive hidden memories, or feed my own thoughts into his head. I amazed and mystified quite a few fellow employees that way. So it wasn’t that everybody thought me a strange duck quacking nonsense.

But as far as SVS was concerned, I’d become a balmy round-the-bender, dotty as a loon. It wasn’t long before I was in the M.D.’s office again.

This time he arranged time off for me so that I could journey with Mum to Pondicherry, where Auroville, the ashram founded by Aurobindo in 1926, was located. We stayed there fifteen days. I got to know M.P. Pandit, a confidante of the recently deceased Mother, quite well. He was impressed with what he thought were my psychic powers. Somehow, from down the ‘tube’, the memory-images of a secretary (no longer in Auroville) who’d typed the Mother’s letters some twenty years before were streaming into my mind. Pandit checked the information I gave him against the letters in the archives and found it accurate.

He asked me to stay, but when I saw meat being served in the dining room, and foreign girls in T-shirts and shorts mixing freely with the men, I declined. Mum, a simple lady who’d never been confronted with loose Western ways before, was scandalized. She couldn’t accept that there was any value in Aurobindo’s teachings after seeing life in Auroville. “The chicken thief comes sporting a feather,” was her way of saying, “Know a tree by the fruits.”

As for me, I simply incorporated what I thought was useful from Aurobindo’s ideas into what I was already doing. Certainly, the daily puja to Aurobindo and the Mother was useful. It saved me my job for the simple reason that the M.D. continued to have faith in me. After returning from Auroville, he let me do pretty much what I wanted. Once in a while, I might actually put in a full day’s work. Other days, I would work for an hour or two, then drift into idle reverie and leave whenever I felt like it. But I continued collecting full pay, much to SVS’s chagrin.

Sri Aurobindo

I’d been sharing an apartment for more than a year with Shankara Subrahmania. He was a jolly fellow who weathered my vagaries well, even when I would sometimes flick on the light at midnight, wake him up and harangue him on some arcane topic for an hour or two.

There was another fellow our age, named Mani, an oddjobber, who lived in the same building. He too thought himself a bit of a philosopher, but one of the world, the flesh and the Devil. As long as I only talked of religion and esotera, he kept away. But when I started to have trouble at work, I began expressing doubts about the course my life was taking.

As fascinated as I was with spirituality, I’d come a to a crossroads with it and didn’t know which way to turn. If I was to again concentrate on a career with TVS, I’d have to give it up completely. But that had become extremely difficult. My mind constantly percolated with clairvoyant visions and I just couldn’t hide it anymore. Coping with the workaday world was becoming a major problem.

When Mani came to know of this, he stepped into my life with his smirking advice. “Listen, Aiyer, you’re in trouble because you aim too high, know what I mean? Trying to be a pukka brahmin, but for what? You’re too clean for your own good. If you want to clear all this hocus-pocus out of your head, you got to dirty up a bit.” He hinted that he “knew just what I needed, and could help me get it.” I feigned disinterest, but Mani persisted day after day, sensing my resolve was crumbling. And it surely was.

Young men everywhere have a fancy for the female form. But in respectable Indian society there is only one acceptable outlet for it, and that is marriage. I’d remained unmarried and avoided scandal, not because of a lack of attraction to women, but because I’d sublimated a great deal of my sexuality with the help of right-hand tantra. I had practiced it for the past five years, and since meeting the little prophetess of Mahabalipuram, I’d become quite strict.

I liked to think of my interests in women as aesthetic appreciations of the divine female principle. I especially enjoyed seeing the movements of skilled female dancers in Bharat-natyam performances. And, having moved among actors, I knew how to capture a beautiful woman’s attention and hold it in coversation. I’d get vicarious pleasure from watching her graceful gestures and hearing her melodious voice. Now and again I’d encourage a woman I liked to become emotionally attached to me so that I could enjoy her affections. But I always tried to keep a proper reserve: they were representations of Devi, and I couldn’t sully my family’s good name with shameful behavior.

By the ritualism of Shakta-tantra, I had ‘mist-tified’ the raging river of youthful male lust into a quiet haze, a curtain of nebulous, dissipated libido that shone silvery white on the outside but drizzled dark and obsessive within. Deep in the foggy interior, fettered by archaic Hindu mores that steadily rusted away in the dampness, the black fiend Kali, human degredation personified, thrilled at every touch, however slight, of the filaments of my consciousness upon the female form – be it Devi or the flesh-meat of pimps, it was all the same in Kali’s night of the soul. And he wanted much, much more than I’d been giving him.

Now Kali had found a voice: Mani’s.

One evening as I sat wasting Shankara’s time, giving him a lecture on palmistry, Mani came to the door, a skinny wolf dressed in what I called a ‘hero suit’, a cheap knock-off of the kind of outfits worn by Bombay cinema heroes. With sly nonchalance he said, “Hey Brahmin, let Shankara get some sleep and come out with me tonight.”

Shankara was only too glad to let me go. We ended up in what I thought was a hotel. But when Mani began negotiations with the manager, I knew immediately it was not a place where you got a good night’s sleep. I took Mani aside.

“Leave me out of whatever you’re arranging, okay?”

He chuckled and hit me lightly on the shoulder. “Right, Brahmin, no problem. You just sit yourself down here in the lobby. I’ve got a little business to take care of upstairs. I’ll be with you in about (here he winked) half an hour.”

Two minutes later a servant boy came down to tell me that Mani needed my help. I followed the boy up three flights of stairs and to a room where I found Mani with two heavily made-up girls in tawdry glamour gowns, perfect compliments for the would-be hero.

He stood between them, an arm around each one. Flashing a big grin as I entered, he sang out, “Here’s the pandit! Brahmin baby, I’ve got two beautiful sweeties here and I don’t know which one to choose. Tell me who’s the best.” The floozies giggled. In jest, I pointed to the one on the left. He steered her over to me.

“You got a real sharp eye for the ladies, panditji. So take her.”

Half-heartedly, I turned to leave. He blocked my way and sneered in my face, “Hey, look, Brahmin baby, I gone through a lot of trouble tonight just to help you out. You wanna get your feet back on the ground? Get those jinnis out of your head? I got the solution for you – a sure cure for the too damn pure.”

I gave in, thinking it my fate, like that of the mouse returned to its kind.

In the Panchatantra, there is a story of a female mouse that was seized by a hawk, carried aloft, and dropped over the river Ganges. Below, the great sage Yajnavalkya was performing his ablutions. The mouse fell right into his cupped palms containing holy Ganges water. By contact with the combined spiritual power of the saint and the sacred water, the mouse was transformed into a baby girl.

Yajnavalkya took the child home and gave her to his wife to raise as their daughter. When the child turned twelve years of age, he thought to arrange the most excellent match for her marriage.

He first summoned the sun-god Surya, who appeared at his ashram. But the girl thought him too blazing hot. Yajnavalkya asked the sun if there was one greater than he. Surya recommended the cloud, because the cloud could cover his rays.

When the cloud came, the girl deemed him too black and cold. The cloud was asked if there was anyone greater than he. He suggested the mountain, who alone could stop his progress.

When the mountain came before the sage, the girl said he was too rough and stony. And the mountain, when asked, recommended the king of mice as his superior, because he and the other mice made holes in him.

When the king of mice was called, the mouse-girl immediately agreed, thrilling with ecstacy. She begged Yajnavalkya to make her a mouse again, and it was done.

Devi, Karttikeya, Brahmendra Avadhuta, Aurobindo – these had been my Yajnavalkya, sun, cloud and mountain. Devi had transformed me with tantra, but I could not be wedded to a ‘great’ who could complete the transformation. Now I was back in the mousehole. I’d gotten warnings from the girl in Mahabalipuram and my friend at the Shivananda Yoga Mission. But whimsy prevented my heeding them. Now whimsy dictated I should revel in this hole I’d fallen into.

I applied the same investigative attitude in this field as I’d had in the others. I moved out of the room I’d shared with Shankara Subrahmania and got a place in Salem’s red-light district. I got to know practically every prostitute in town, not simply to slake my flesh, but to study the consciousness of prostitution: the stories of the girls’ lives, their dreams, their fears.

There was one who was very different from the rest. She was a high society girl who lived with her mother in a well-furnished home in a wealthy neighborhood. She was beautiful, intelligent, an expert conversationalist, a talented singer, and went by the Sanksrit name Charulata (‘Moon Vine’).

Only rich businessmen could afford her. I didn’t have that kind of money, so I used to visit her just to talk. In her I found a sympathetic friend like I’d never had before – one with whom I could speak freely from the heart, and whose advice was always sincere and helpful. For someone as wretched and misunderstood as I was at this stage of my life, Charulata was like an exotic, perfumed houri descended from the heaven of the prophets, sensuous yet angelic, full of grace and understanding. And she found a shelter in me, for secretly the life of a prostitute disgusted her. I was the only person she dared confess this to. Our friendship soon deepened into love, though we could not admit it to each other.

Charulata’s mother was herself a former prostitute who acted as her manager. The mother didn’t care for my visits since I only wasted her daughter’s time without paying for it. But over the weeks, I scraped and saved enough money to finally be able to consummate our relationship. One day I pressed a thick fold of notes into the old lady’s hand and told her to get lost for an hour. She scurried to her daughter’s room to have a quick word with her, and then left the house.

I found Charulata ashen-faced and trembling. “M-mummy said y-you want to …” was all she could say before bursting into tears. Covering her face with her hands, she dropped into an upholstered chair and bent her head to her knees, her shoulders heaving with sobs.

I was aghast. “What’s wrong with you?”

Her words escaped in gasps from between pitiful cries. “I can’t do this sin with you – I only wanted to help you – I thought I might change you – now it has come to this – please go away.”

My knees were sagging. I felt helpless, stupid, and cheated.

“How are you going to change me, Charulata? Who do think you are? You’re not my wife, sister, or mother. You’re a … well, we both know what you are. So who are you to tell me to leave? I’ve paid your mother, and I’ve come to have what’s mine.”

Still bent double, she wailed and shook her head, refusing to look at me.

I touched her shoulder; she jumped out of the chair and slapped me. Racked by uncontrollable sobbing, she moved back unsteadily, her eyes swollen, makeup running, hair scattered and tangled. I tried to say something, but she cut me off, her voice choking.

“I always thought of you as a saintly person. I considered myself your disciple. I never saw you like the others. You’re not meant for this filth!”

“You’re mad, Charulata. You know I visit prostitutes all over the city. How can a man like me be saintly? What’s come over you?”

She sank into another chair and wiped the tears from her eyes with the end of her sari. Gradually regaining her composure, she spoke of a Vaishnava saint named Bilvamangala, known as Lila Suka before he renounced the world.

“Lila Suka had a courtesan named Chintamani. When he came to her in the middle of a stormy night, she rebuked him, saying ‘If you were as attached to God as you are to my flesh and bones, you’d be a liberated soul.’ He took her words as divine and went to Vrindavan, the holy land of Krishna, and surrendered himself to the Lord’s service. I am begging you, Kannan, please likewise take my words as divine – and go.”

“You’re not being fair. Any other man can walk in here with money and have your body. But to me, you say this.”

Her hands were in her lap now. She studied them for a moment. Then she looked up at me, eyes large and somber, her mouth set in determination.

“This is the end of it, Kannan. I cannot go on another day with this life of sin. Now you have to make the same decision in your life. Don’t come back here again, because you won’t find me.”

I turned and walked out onto the quiet, tree-lined street. I didn’t know whether to laugh, cry or fling myself off a bridge. My head pounded with insane echoes of my useless, useless life. The world trembled, its imagery crazy and disconnected, like glass shards hanging in the frame of a shattered mirror.

Word had gotten around of my prostitute-hunting, and though I didn’t mind so much the ribbing I had to take for it at work, it was an embarrassment to learn that my mother had found out. While I was at home on a weekend visit, she delicately brought up the subject of marriage.

“I’ve made an arrangement for you, Kannan. A nice girl…”

“Oh, you mean the girl from the Iyengar family?”

Mum blinked. “Yes, er … how did you know?”

The ‘tube’ was buzzing with the news. I told Mum the name of the girl and the address of her home. I even described the sacred pictures her family kept on display inside. When we arrived at the family’s house (which Mum had not yet visited), she was shocked to find that everything within was as I said it would be.

Unfortunately for my poor mother, the impression I made on the family was so peculiar that the marriage proceedings died in the egg. Afterward, she was more disgusted with me than I’d ever seen in my life. “You should commit suicide,” was all she could tell me. For an Indian woman, that was probably the strongest rebuke she could make to a son.

I’d hardly reached manhood and had become a shambling clown, despised even by my own mother.

Parts in this series:

Chapter 1: Exposure to the Tantric Path

Chapter 2: Secrets of Left-hand Tantra

Chapter 3: The Gate of Dreams (Tantrics of Kerala)

Chapter 4: The Self in the Mirror

Chapter 5: Again a Mouse

Chapter 6: I become ‘Swami Atmananda’

Chapter 7: With and against Sai Baba

Chapter 8: Odd Gods of the South

Background information: These stories are biographical narrations by the author, written down around 20 years ago. This was originally meant to be published as a book, but after completing the first eight chapters, the author chose not to continue, and thus we are left with the stories in their present incomplete form. Most of these stories took place around 1970. The areas discussed in these stories have changed greatly in the last 40 years and may not match what we see today. All of these stories are factual. There is no plan to ever publish this book, so if you want to know more, or if you want to know about other events that occurred, you would have to meet the author personally.

Very interesting and well written would like to talk to the author!

I don’t understand how Kali, and her black night has anything to do with this man succumbing to this Mani whore-monger character. What has Ma Kali And her black night have to do with destructive and sinful behavior? Maybe if this person has listened more closely to the Yogi and Bala Devi, and followed the path of Bala worship this whole prostitute business would have never come about. However I am not passing judgement, only making observation. When Maa in physical form tells you something, it’s ultimately with motherly love, even if it’s in the form of a child she is speak, which can only mean it’s best for you. She told this person in loving kindness what to do to avoid this path of prostitutes and lust. Not everyone is so fortunate to receive such a Darshan.

Note the pronoun used: “he”

The author is referring to Kali Purusa not Kaaaali Ma.

May be this man is suffering without taking Bala Tripurasundari’s invitation in to sudda vidya. Iam really longing for an opportunity to see her in human form altleast before my death. iam a srividya upasak who belives in matha , pity on this story who lost all good opportunities ..

How can I reach to the author of this un-published book ? Is it possible for me to contact him by e-mail, phone call or post ?

I believe, the author was right in rejecting the Tantrik, Adwaitvaadi, Saai Baaba, Sri Aurobindo etc. Based on my own experience, I would like to add that search of Guru for the whole life is simply futile. Even Narendra Modi our PM in his young life went to Himalayas in search of Guru but then return. Fact is when disciple is ready – Guru picks him up.

Thumb rules to find out true Guru:-

1) Check whose disciple he is ?

2) Check if he is exactly following the foot-steps of his own Guru !

3) Check if he is capable to keep himself away from both women and money !

4) Check to what extent his followers/disciples are living the life exactly as per

the expectations of their Guru.

Tell me the names of such Guru you know as on date. Here follows the check-list

answers for my own Guru Pramukh Swami Maharaj.

1) He is disciple of Shashtriji Maharaj & Yogiji Maharaj.

2) For past 93 years, he has followed exactly as per the foot-prints of his own

Gurus. He has lived life exactly as expected of him by his own Guru.

3) He is head of BAPS, yet he neither has any bank account nor he has touched

any currency notes ever since he became Sadhu and renounced from this world.

4) As Sadhu, he neither talks or looks at any woman

5) One of his disciple in Bahrain resigned from partnership of the Company and

now became employee of the same Company. Another disciple in Ahmedabad

stopped his own successful Medical practice and accepted job at local Civil

Hospital for meager monthly salary. Why ? Just because to do as per the

instructions of their Guru Pramukh Swami Maharaj.

Bottom line is, you can judge a true Guru by looking into life lived by his own Guru as well life lived by his disciples.

Mr.Iyer is in learning process.He could not win prostitute byhis physical glamour or money.The women is another Chintamani.One student of swayam……swamiji need not surrender to Shri aurobindo&mother due to his director.When his mother cursed him,he should know where he stands?Anybody cannot tell but he should realise constantly if he got RUCHI for knowing{realising}himself.

umashankar,sr.citizen{age is not criteria}

mystic and interesting