Along with the magnificent temple artifacts found in Central Java, the sculptures at Angkor Wat offer an amazing visual record of many famous transcendental pastimes. The Churning of the Milk Ocean is one such inconceivable pastime that is described in the epic Mahabharata.

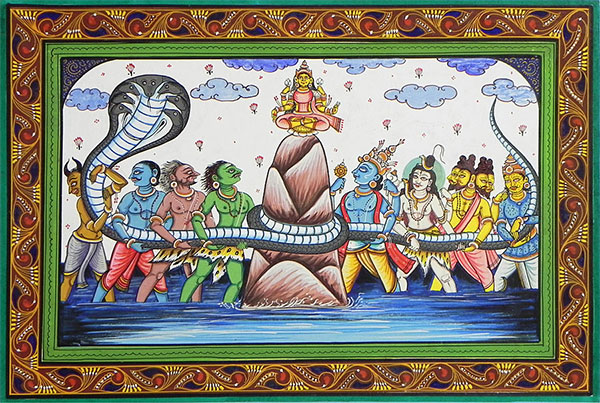

The Churning took place at the beginning of the Golden Age (Krta Yuga), at which time the celestial forces of light (Devas) and the forces of darkness (Asuras) agreed to cooperate in an effort to generate the elixir of immortality known as Amrita by churning the great ocean that surrounded the planet. The Demigods uprooted Mount Mandara (Sanskrit for “cream” or “clarified butter”) from its resting place at the Earth’s north pole, and transported it to the center of the great Milk Ocean.

The celestial king of the naga serpents, Vasuki, consented to allow his body to be used as the churning apparatus. Lord Vishnu, in His incarnation as Kurma Avatara, assumed the Form of the king of tortoises, Kurma, in order to support the pivotal mountain on His back. This prevented Mt. Mandara from sinking beneath the ocean waves.

As the Devas and Asura engaged in their cosmic tug of war, the trees covering Mandara’s slopes crash into each another and burst into fire, which causes a black cloud to hover over its peak. The magical herbs that grew on the mountain combined with the resins of the trees, creating a river of juices that flowed down into the great ocean, transforming it into a Sea of Milk.

Despite their best efforts, the demigods and demons were unable to generate the Amrita. When the churners grow weary, Vishnu granted them the strength to complete their churning task. Eventually a Sun of a hundred-thousand rays emerged from the ocean accompanied by the Moon, which radiated its tranquil, cool light. These celestial orbs were followed by the Goddess Sri, the Goddess of nectar, a White Horse, and the resplendent Kaustubha jewel that Vishnu thereafter wore upon his breast. The celestial procession was completed when the divine physician, Dhanvantari, emerged from the Milk Ocean carrying a white gourd that contained the Amrita.

In her book, “Angkor Wat: Space, Time and Kingship”, author Eleanor Mannikka attempts to demonstrate the many ways in which the temples of Angkor symbolize the Churning Saga in material form. Within the bas-reliefs located on the east-facing wall of the main temple of Angkor Wat, for example, the pivotal axis is occupied by Vishnu, who directs the teams of devas and asuras as they strain in their attempt to Churn the elixir of immortality. The research of Ms. Mannikka also indicates a correspondence between Vishnu’s role as the celestial pivot and the reigning king as the pivot of the kingdom.

According to the author, the figures that are portrayed in the relief of the Churning of the Sea of Milk at Angkor Wat also collectively represent the number of days between the Winter and Summer solstices.

“In the bas-reliefs at Angkor Wat, the position of the churning pivot would correspond to the position of the Spring equinox. The 91 asuras in the south represent the 91 days from equinox to winter solstice, and the 88 northern devas represent the 88 days from equinox to summer solstice. In fact, there are either 88 or 89 devas in the scene, 89 is the Deva atop mount Mandara is counted with the others. There are 88 or 89 days from the spring equinox, counted from the first day of the new year, to the summer solstice.”

“In Cambodia, the spring lasted for 3 or 4 days…. Mount Mandara as the churning pivot would symbolize the 3 or 4 days of the equinox period, the northernmost Deva would represent the summer solstice day, and the southernmost assure would correspond with to the winter solstice day. In other words, the scene is a calendar. It positions the two solstice days at the extreme north and south, counts the days between them….”

Elsewhere at Angkor, the Churning of the Milk Ocean has more often been numerically expressed through the representation of two groups that each contain 54 images, or 108 in total. This numerical theme is in evidence at each of the five gates leading into the ancient city of Angkor Thom. On either side of the roadway, the images of 54 asuras and 54 devas can be seen tugging on the body of a massive naga serpent. The gateway tower that serves as the pivot of the churning tableau is crowned by a head with four faces that gaze outward toward the cardinal points.

Ms. Mannikka accounts for the numerical discrepancy between the Angkor Wat reliefs and the symbolism at each of the city gates by noting that 108 is the most sacred number in Hindu/Buddhism cosmology. However, an alternate explanation can be tendered that not only takes into account a solar cycle that is relevant to Angkor’s geographical location, but also one that can equally be applied to Prambanan as a possible explanation for why its central courtyard is surrounded by a total of 224 smaller temples.