Background Information:

These stories are biographical narrations by the author, written down around 20 years ago. This was originally meant to be published as a book, but after completing the first eight chapters, the author chose not to continue, and thus we are left with the stories in their present incomplete form. Most of these stories took place around 1970. The areas discussed in these stories have changed greatly in the last 40 years and may not match what we see today. All of these stories are factual. There is no plan to ever publish this book, so if you want to know more, or if you want to know about other events that occurred, you would have to meet the author personally.

Chapter Six

It was the end of June, 1974. As per a recent agreement with the workers’ union, the company was to dispense a semi-annual cash bonus along with this month’s regular pay allotment. Our department’s job was to do the calculation of each employee’s bonus percentage. But two of our men had gone on leave. SVS was in a fix – how would all this work be finished before payday, tomorrow?

I bailed him out by working late, doing the jobs of three men, including the arithmetic, the counting of the cash and the sorting of the pay envelopes. Shortly before ten o’clock, the night watchman came by the office and looked in.

“How can you finish all this tonight? Is it that you’re not coming to work tomorrow?”

I brushed him off with a confident grin, assuring him that I was nearly done and there were no problems. Nodding, he ambled out. But his suggestion that I would not work here tomorrow sunk in.

Right then and there my determination to go on with life as I’d been living it crumbled around me. I’d been visiting as many as two prostitutes a day while keeping up a phoney mystical aura about myself. All I had done was make myself look ridiculous to Charulata, the only person who really mattered to me. Even Mum was fed up. And on top of that I was caged like a wild beast in the TVS organization. I wanted out.

I completed the work at ten. I signed the register for my own pay envelope and pocketed it. The watchman let me out of the building and through the security gate onto the street. I stood in front of the factory for a moment, gazing at its monolithic bulk that seemed to glow a sinister dull red under the harsh spotlights. “Not in this lifetime again”, I swore under my breath.

I took an autorickshaw to my apartment in the brothel district. My roommate at this time, Mr. Joseph, was the headmaster of a Christian school. It was his habit to get drunk every evening, and this evening he was dead drunk. I found the door to the apartment ajar, and him sprawled out on the floor with a bottle still clutched in his fist.

I left a note on my bedroom mirror to whomever would come looking for me on behalf of the company: “Please don’t look further. I have left Salem. If I ever become useful I will come back.” I extracted ten 20-Rupee notes from my pay envelope and scribbled a message for Mr. Joseph on the back: “Please send this money to my mother.” Pocketing the Rs. 200, I lay the envelope and my apartment key on the floor mattress in his room; I knew this was one task old Mr. Joseph could be trusted with. After all, he was a good Christian.

I tiptoed around his snoring form and exited the apartment, closing the door softly behind me. It was almost eleven. The front door of the rooming house faced a through-city highway on which express busses to Madras drove. Waiting under a flickering defective neon tube struggling for its life amidst a swirling cloud of bugs, I was only half-aware of the raucous night life that swirled around me.

Soon a bus came and I stepped out into the street and waved it down. A skinny wooly-headed conductor with a few days growth of beard opened the rear door. I tried to enter but he blocked my way. “You’re going to which place?”

I asked back, “Well, where does the bus go?” He repeated his question and I repeated mine.

He cursed and shouted, “What a stupid conversation for this time of night! Just get in here!” I boarded and the bus roared off. After half an hour of eyeing me strangely, the conductor sat down on the next seat and said with a nervous laugh, “I think now you’ll tell me where you’re going, isn’t it?” In a wooden voice I replied, “I’m still asking you where this bus is going.” He shook his head as if talking to an idiot and sighed wearily, “This bus is going Arakkonam.” I paid the fare without further comment.

We pulled into Arakkonam shortly before dawn and I disembarked in front of the railway station. Nearby I saw a hotel with a spear painted over the entrance; the signboard said ‘Shakti Vel.’ The only availability there was a single room with a common bath and toilet down the hall. I took it.

I had no luggage with me, just the pants, kurta and slip-on shoes I was wearing, and my money. Dazed from the night journey and my own inner distress, I sat listlessly in the dingy room for a while. Then I thought of going to the bathroom. Stepping out into the hall, I noticed that a light was on in the room opposite mine. I heard a mother talking with her son and daughter inside – and I recognized the voices. This was the family of my uncle Bala Subrahmanian from Kerala!

I froze, my heart pounding. Listening at their door, I could understand they were on their way to the pilgrimage town of Tirupathi to visit the famous Venkateshwara Swami temple, some seventy-five kilometers north of here. They would soon depart the hotel by car and would pay a quick visit to a Kartikeya temple just beyond Arakkonam at a place called Tiruthani. If they saw me now, my plan of leaving everything would fail. I withdrew silently into my room and sat on the edge of the bed in total anxiety, thinking, “Why did I come to this town? Why did I take this lodge?”

At seven o’clock I heard them leave. I rushed into the bathroom with a bursting bladder, relieved myself, and then went downstairs to tell the man at the desk, “I’m vacating.” His jaw dropped. “What! You just arrived!” I paid and walked out onto the sunlit street. The small town center of Arakkonam had come to life with jingling bicycles, honking traffic and a group of marching pilgrims singing songs in praise of Kartikeya.

These pilgrims were villagers on their way to visit Tiruthani. Some of them carried kaveri, gaily decorated boxlike structures made from light wood. These they supported on their shoulders to ceremonially transport brass pots of water or milk meant for offering to the murti. I apathetically fell in step with them, having nothing else to do. Singing and dancing around me, they swept me along.

It wasn’t many minutes before we had left Arakkonam behind. The pilgrims kept up their celebrations as we trekked across the arid, treeless landscape. Though the asphalt road we followed sometimes brought us near rocky hills that abruptly reared a hundred meters or so up into the brilliant morning sky, the land here was generally flat, and appeared uninhabited.

After about an hour we came to Tiruthani Temple, situated on the peak of a hill. A big stone stairway rose majestically from the roadside to the entrance gate. The temple was crowned by a distinctively-shaped vimana (main tower) signifying that the deity within is Kartikeya. Around the building stood a high wall painted with red and white vertical stripes, a feature of many temples in South India.

Tiruthani means “the lord’s garden”. Lord Kartikeya is believed to have landed here from Kailash (the heavenly abode of his father Shiva) and taken a little rest in a garden at the top of this hill before going to the ocean shore at Tiruchendur to kill the demon Surapadma.

I climbed up the stairs with my companions who now sang prayers asking favors from the murti. I was numb, almost catatonic when I got to the top. “What is my life for?”, I moaned half-audibly.

At this point religion, philosophy and mysticism meant nothing to me, despite all my high-flown pretentions of the past. I was utterly frustrated with myself. I would have welcomed death had I believed it would really end my existence forever, but I feared rebirth even more. In a way, I yearned for something that would lift me to a higher state. But at the same time I doubted there was any hope for me.

Now inside the temple’s dark massivly pillared interior, the pilgrims were respectfully silent. I shuffled listlessly before the murti of Kartikeya. He stood between his two wives Valli and Devasena, the three of them black and glistening in the glowing lamplight. The priest chanted a prayer that said “May all the bad results of sinful deeds be destroyed by your spear.” With my eyes shut tight in desperation and my palms pressed together before my face, I prayed: “Please give me some direction.”

I stumbled out into the bright sunshine with a buzzing head and wearily started down the stairs. At a small mandapa I saw an wizened old begger sitting in the shade. I sat down next to him and we started talking. He asked me “Where are you going?”, just as I asked him, “Where should I go?”

He looked at me a little startled, working his toothless jaws. “You are asking me?”

“Yes. I don’t know where I should go at this point in my life.”

“Then go to Tirupathi.”

“No, I don’t think I should go there, because someone who will spoil my plan has just left for there.”

“No, no, don’t worry about that!” he snorted. His conviction caught my attention. “You must go there. Your plan will become successful; no one will stop you.” He then quoted a poetic couplet:

“When Kartikeya was dissatisfied by not getting the fruit, he came to the south.” This referred to Kartikeya’s losing a test of wits to his brother Ganesh, who received as a prize a fruit from the hand of the sage Narada; in frustration, Kartikeya retired from Kailash to Tiruthani, in South India.

Tiruthani

“Kartikeya went south,” the old beggar continued, “but you – you go north.”

I gave him a few coins and walked to the bottom of the stairs, got on a northbound bus and rode across the Tamil Nadu-Andhra Pradesh border to Tirupathi. All the way I glumly mulled over why I was bothering to make yet another pilgrimage to see one more mute stone idol.

Venkateshwara Swami is one of India’s most popular Vishnu deities. He is known by the name Sri Balaji to pilgrims from the north, but Srinivasa is the name we southerners prefer. Srinivasa means “the Abode of Sri”, Sri being Lakshmi, the Goddess of Fortune.

According to the Ramayana and the Puranas, in ancient times Lord Vishnu descended to earth from the spiritual realm as Prince Ramachandra. His consort Lakshmi descended as the beautiful Sita, Rama’s wife. When the demon-king Ravana attempted to kidnap Sita, the fire-god Agni tricked him by substituting Vedavati for Rama’s spouse. Thus Ravana took Vedavati with him to his island kingdom of Lanka, thinking she was Sita.

Vedavati was actually an illusory form of Lakshmi. She had previously appeared as a princess over whom Ravana had lusted; she flung herself into fire rather than endure the demon’s attentions. As she disappeared into the flames, Vedavati placed a curse on Ravana, saying she would return to destroy him and his dynasty. But as the divine energy of Lord Vishnu, she was not burned. Agni kept Vedavati with him and they waited for Ravana to make his move against Sita. When Ravana abducted Vedavati, mistaking her for Sita, the real Sita was then sequestered with Agni.

It was Rama’s purpose all along to destroy Ravana and his race of man-eaters. Accepting the mood of a husband whose beloved wife was in great peril, Rama attacked Lanka and destroyed Ravana and his kinsmen. But after recovering her, Rama ordered her to enter fire, as she had been defiled by the touch of a sinful demon.

Ever-faithful, she did as she was told – and Agni emerged from the flames bringing with him both the real Sita and Vedavati. Though Agni requested Rama to accept Vedavati as a second wife, Rama refused, saying, “I have vowed in this descent to have only one wife. I will accept Vedavati when I appear on earth as Srinivasa. She will then be known as Padmavati and be my bride.”

As Srinivasa, Vishnu wed Padmavati. But Lakshmi (Sri) came to disturb the marriage, claiming it was invalid because Srinivasa is always hers. As Sri and Padmavati quarreled, Srinivasa took seven steps back and became a murti. The heartbroken goddesses wailed in sorrow, but Srinivasa consoled them by telling them that they were both expansions of the same spiritual potency, the Vishnu-shakti. The two goddesses embraced each other and then stood on either side of Srinivasa. Indeed, Lakshmi and Padmavati assumed murti forms themselves.

The Venkateshwara temple is a magnet that yearly draws millions of pilgrims from all corners of India. A common sacrifice these pilgrims make is head-shaving, which is done by man, woman and child alike. The temple collects hundreds of millions of rupees in donations; much of this money is used to help the poor and provide facilities for pilgrims.

But in my dejected cynicism I wondered, “How is it that a stone in Tirupathi can attract so many pilgrims? Someone was really clever to think up this money-making gimmick.”

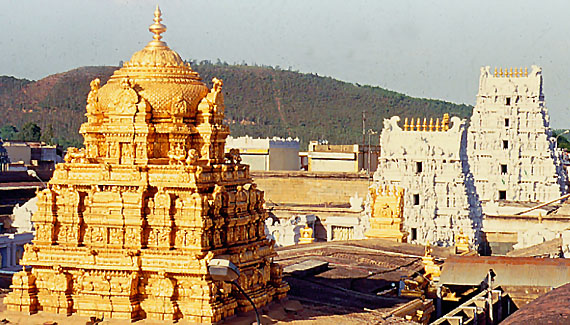

I arrived in Tirupathi around noon. I boarded a link bus that ferried pilgrims to and from the top of Tirumala hill where the temple and the surrounding complex is situated. The complex is truly a city in itself, for a staff of thousands – priests, administrators, workers and their families – permanently resides there. In addition, there are never less than five thousand visiting pilgrims, and often many more.

After leaving the Tirumala bus stop and passing by well-kept blocks of adminstrative offices and pilgrims’ guest houses, I turned down a wide paved walkway lined by stalls where all sorts of goods were proferred for sale. At the end of this bustling bazaar loomed the gopuram, an ornately carved tower that soared high over the front gate of the temple.

A queue of pilgrims stretched from the cavernous entrance around the side of the wall and back into a series of waiting halls, all filled. I took my place at the end. It was two and a half hours before I got to the Deity.

But in spite of the long wait, I felt my despair fade. It seemed as if I was being inexorably drawn deeper and deeper into a divine mystery as I slowly shuffled along in line past the ancient, intricately carved stone-block structures that marked our approach to the sanctum sanctorum.

I found the mounting ecstacy of the faithful pilgrims around me infectious. As we ascended the few stone steps that brought us up from a vast court into the doorway of the Deity’s residence, the excitement of the devotees burst around me in chants of “Govinda! Govinda!” We quickly moved through the crowded entrance area and down the right side of a long corridor that led directly to Srinivasa, suddenly visible over the heads of the throng in front of me.

The line moved swiftly forward. I kept my eyes fixed on the Deity and felt an awesome power drawing me closer and closer that seemed to have nothing to do with the physical factors of the forward motion of the crowd. I was entering into an intense personal exchange with Transcendence.

At the end of the corridor I came before Srinivasa, black in color and bedecked with silver, gold and jewel-encrusted ornaments. The upper portion of the Deity’s face was covered by Vishnu tilak, a U-shaped white marking worn on the forehead. The bottom of the “U” should normally just cross the space between the eyebrows, but a distinctive feature of this murti is that the tilak is oversized and covers the eyes. He wore a high conical silver crown topped by a rounded peak. His decorations shimmered prismatically in the light of the votary lamps.

In the brief moment I stood before Srinivasa, I was moved by the remembrance of my mother’s exclusive and abiding devotion to Vishnu as the complete form of the Supreme Truth, which other forms like Shiva and Durga only partially represent. A verse from the Bhagavad-gita crossed my mind: “Abandon all varieties of religion and just surrender unto Me. I shall deliver you from all sinful reaction. Do not fear.”

The darshan area in front the sanctum sanctorum was supervised by young but stern-looking ladies who briskly ushered the pilgrims past the Deity, sometimes with shoves between the shoulder blades of those who lingered too long. I dared not tarry. I turned and followed the queue back up the other side of the long corridor to the exit, looking over my shoulder to get yet another glimpse of Srinivasa. Leaving the residence as quickly as we had entered it, the queue continued on its route through the temple compound to the front gate.

Coming out of the temple from beneath the gopuram, I wandered into the bazaar again. Jostled by the teeming shoppers, I reviewed the emptiness of my life. Just as I was being pushed to and fro in this marketplace, so I had been pushed from one fruitless venture to another, with nothing to show for it. Remembering the Bhagavad-gita again, I decided I must attain that state of deliverance from all reactions to my foolish deeds. I would surrender myself to spiritual life and become a sadhu, a wandering holy man.

From a stall dealing in North Indian clothing I bought lenga (loose-fitting pyjama-like trousers) and a four-meter length of cotton cloth. From another place I got some turmeric. Then I went to the Swami Pushkarini, the large sacred bathing pool next to the temple. Using the turmeric as dye, I colored the trousers and long cloth yellow and set the trousers out to dry.

I got my head shaved by one of the straight-razor barbers squatting on the concrete steps around the pool. Removing my clothing, I wrapped myself in the long cloth and immersed myself in the holy waters, dipping three times. As I came out, a man passing by paused to apply a dab of moist white clay from within a small brass bowl in his hand to my forehead, deftly making the tilak mark with one stroke of a finger. I took this as a sign of the Lord’s acknowledgment of my desire to surrender.

After I and my yellow-dyed clothing had dried, I donned the lenga and wrapped my head turban-style with the middle part of the long cloth, bringing the two lengths of excess down from the back of my neck over each shoulder. I crossed the lengths at the chest and tied them around my waist.

I placed my old shirt and pants in the bag I’d gotten from the cloth stall and left my slippers at the pool. I still had 150 rupies. I decided to donate this to Srinivasa.

At the temple entrance, I saw the counter for the “special darshan” costing twenty-five rupees. This allowed one to cut his waiting time in the queue to around a quarter of an hour. I decided to have six special darshans and exhaust my money.

Coming before Srinivasa the sixth time, I noticed that I was still carrying the bag of old cloth in my hand. In my mind I asked the murti, “You are known as Hari, ‘He who takes away our material attachments’. How will You take this bag from me?”

As I exited the long corridor and entered the front room of the residence, I noticed a bearded brahmin sitting in a cordoned-off area there. He was big-bodied and bare-chested, his forehead, torso, arms and spine adorned with twelve tilak marks, signifying him to be a temple priest. He was grinding paste from a block of moist sandalwood by rubbing it on piece of flat sandstone. I broke from the line and kneeled down near him to watch. The sweet-scented sandalwood paste mixed with a little saffron or camphor was applied to the body of the murti as a refreshing cosmetic. But this was usually done just after the early morning bathing ceremony; now it was mid-afternoon.

I was just going to ask him if there was a special puja (worship) about to happen when he looked up at me and asked, “What do you have in that bag?”

“Oh, just some clothing,” I said, opening the bag so that he could see.

Noticing my old kurta, a style of shirt not often seen in South India, he said, “This shirt is very nice. If you’re not needing it anymore, can you give it to me?”

I protested, not wanting to give a temple priest my old caste-offs. But he was so insistent that I relented on the condition that he arrange a special darshan of Srinivasa for me, one in which I could stand as long as I liked before the Deity.

He readily agreed. He set the bag on a nearby shelf and took me firmly by the hand, leading me through the crowd to the long corridor.

The length of the corridor was divided down the middle by a special aisle about one meter wide that was sectioned off from the rest of the corridor by metal hand rails. This served a double purpose: it separated the incoming queue from the outgoing and allowed authorized persons a free route to the darshan area. One could enter this aisle through a metal gate where the donation box stood. A police guard in an olive drab uniform and beret was posted nearby.

The big bearded brahmin unlocked the gate with a key dangling at his waste and led me into the aisle between the rails. He strode ahead, pulling me behind him until we came to the darshan area where the pilgrims passed between us and the Deity.

Tirupati Balaji

He stood next to me while I viewed Srinvasa to my heart’s content. I wanted to indelibly impress my mind with the form of the Lord, so I began by meditatively studying each part of that form, beginning with the feet. I gradually brought my eyes up to the Lord’s two hands, the left one held in the mudra of pushing down misery, and the right one in the mudra of benediction. In another two hands the symbols of Vishnu (the disc and the conch) were held just above shoulder level. I studied the slightly smiling expression on Srinivasa’s face and wondered if it indicated satisfaction or amusement, or perhaps something even deeper. Again I moved my eyes back to the feet of the Lord and repeated my meditation twice over.

After that I studied Sri on the Lord’s right and Padmavati on His left. And then I took in the whole scene, the backdrop, the floor, the ceiling. I estimated I’d stood there for five or six minutes.

Finally I looked at the brahmin. He nodded his head and turned. Halfway back to the gate he motioned that I should slip over the handrail and leave with the line of exiting pilgrims. I did so, and he went ahead to the gate and let himself out.

When I got to the front room, I went back to his place, wanting to thank him before I left. But he was not there. Nor was my bag on the shelf. Nor was there even any evidence that he’d been making sandalwood paste some minutes before.

A little confused, I went to two other brahmins who were sitting nearby. “Excuse me,” I spoke politely, “where is the bearded brahmin who was here a short while ago?”

They eyed me a bit strangely. “Bearded brahmin?” snorted one. The other laughed, “You think this is a Shiva temple?” True, I reminded myself, Vaishnava brahmins don’t wear beards.

“He was making sandalwood paste over there,” I pointed. One of the brahmins shook his head. “No, that’s not done at this time. You’ll have to come back at six tomorrow morning if you want to meet the brahmin who does that duty. He’s gone home hours ago.”

I was beginning to wonder if I was dreaming now or had been dreaming when I was with the man with the beard. “But he took me to have darshan through the gate. Didn’t you see me?”

They both looked at each other and chuckled. One said, “We couldn’t help but see you, because we’ve been here the whole time. You went through the darshan queue again and again. We thought you were mad. But you were not with a bearded brahmin, and you did not go through the gate.”

Leaving them joking merrily between themselves, I went to the guard and asked him if he’d seen me go through the gate. “Don’t waste time here!” he shouted in Telegu. “Move along!”

“Please, just give me a moment,” I implored. “I was brought through this gate a few minutes ago by a brahmin, and you were standing right here. Didn’t you notice us?”

“And who do you think you are, the peshkar (head priest)?” he sneered. “It’s my job to make sure only VIP’s get through this gate. And you don’t look like a VIP to me.”

“Well, in that case I think a miracle has happened,” I gulped. He motioned me to the door and told me brusquely, “People have visions here every day. That’s nothing special. Go home and don’t worry about it.”

I came out of the residence in a daze.

Passing through the pavilion where prasadam (sanctified food offered to the Deity) is distributed, I accepted a plate of rice and dahl beans as my first bhiksha, or begged meal. I vowed from then on to live only by begging, and named myself Swami Atmananda.

After leaving the temple compound I returned to the bazaar, moving in the direction of the bus stand. I had to push through swarms of newly-arrived pilgrims excitedly rushing to the darshan queue. Finally I reached the thoroughfare where I saw some share taxis picking up passengers for the ride downhill.

There were eight people in a car closeby; a man called to me from the back seat and asked, “Would you like a ride down with us?” “Yes I would,” I answered, “but I have no money.” He waved me over as the door opened: “I’ll pay your fare, just come.”

I squeezed in and we started down the winding road to Tirupathi. All the way I was absorbed in deep contemplation on what had happened to me in the temple. I asked myself who the bearded brahmin could have been: “Perhaps Srinivasa come in disguise?” I doubted that. He surely wouldn’t personally look after such a wretch as I.

My old skepticism reasserted itself: “The whole thing was imagination.” But I clearly remembered standing before the sanctum sanctorum for several minutes. So many pilgrims passed between where I was standing and the murti. I could still see these people in my mind’s eye with their various dress styles from all over India, and the many shaven-headed women, all being hurried along by the female attendents. As I mused this over, I realized another very strange thing: I couldn’t remember the form of Srinivasa at all. Just the silver conch and disc. The rest was … blocked.

“Well, maybe I didn’t really stand there so long,” I fitfully surmised. But I simply could not convince my intelligence that it did not happen. After all, the bag full of clothing was gone. I recalled how I had mentally challenged Srinivasa to take even that last possession away; mysteriously, my challenge had been met.

At last I just shook my head and smiled to myself. With a glow of inner satisfaction I thought, “I don’t know how, but today I’ve been liberated.” I had to admit that despite all my doubts this clever trickster Lord Srinivasa had definitly changed my life for the better. I felt spiritually purified, completely refreshed and, for the first time in perhaps years, optimistic.

The taxi stopped at the bottom of the hill next to a huge statue of Hanuman. Everyone got out, they to eat at a roadside kitchen and I to begin my wanderings as a mendicant. I walked the rest of the distance to Tirupathi town and stopped at the Govindaraja Swami Perumal, another beautiful Vaishnava temple. I stood before the Deity with my palms pressed together before my chest. “Now I am finished with material life”, I vowed. “Now my spiritual life must begin.”

As I left Govindaraja, it crossed my mind that I knew precious little about spiritual life except that a swami should beg for his needs. I had so much to learn, and needed someone to learn it from.

Nearby I noticed a police station. I walked in, found a well-built, mustachioed inspector at his desk and sat down in front of him. He looked up and, seeing my sadhu dress, asked respectfully, “How can I help you?” I noticed a portrait of Sai Baba on the wall of his office and took this as an opportunity. “I want to go to Sai Baba’s ashram. How can I get there from here?” Under the inspector’s glass desktop cover I spied many more Sai Baba photos.

He brightened visibly upon hearing me mention Sai Baba and replied enthusiastically, “You go from here to Anantapur by bus, then change buses there for Bukkapatnam, and there catch the bus for Sai Baba’s Ashram.”

Thanking him, I pushed back my chair to rise. Then I paused, and choosing my words carefully, took the first hesitant step in my new “spiritual life.”

“Excuse me, but I have no money. Would you be able to help me in meeting the expense for this journey?”

His smile did not waver. “Oh, I am very happy to send someone to Sai Baba, the avatar of the modern age. But I have nothing here. Just go down the road until you see a shop called Srinivas Wines. My wife works there – you tell her I sent you for bus fare to Sai Baba’s Ashram and she will be most happy to give it to you.”

Following his directions, I soon came to the wide entrance of a shop that opened to the street without a front wall or door of any kind. A considerable variety of shapes, sizes and colors of bottled liquor was shelved inside; the walls behind the shelves were mirrored to make the stock look twice as voluminous. Above the entrance I read the red and white sign: “Srinivas Wines”.

In the back of the shop, under a framed and garlanded color poster of Lord Srinivasa, sat a fat lady in a sari. I stepped inside and greeted her with “Sai Ram”, the motto used by the Baba’s followers. She returned the “Sai Ram” and politely gave me a seat. I told her why I’d come and she was very moved. Opening a drawer, she took out a wad of notes and placed it in my hand.

“May I send somebody to get the ticket for you and bring you to the bus?” she asked humbly, eager to do more service. “No need,” I replied dismissively, getting into the feel of a swami’s aplomb. “Your husband’s directions will be sufficient.” As I stood up to leave, I momentarily saw my face reflected among the wine bottles. My Vishnu tilaka had rubbed off, and with my big turban and confident air, I looked like the famous Swami Vivekananda.

The way to Sai Baba’s Ashram proved to be rough. I got on the Anantapur bus at 5:30 PM and it drove the whole night before arriving at the last stop, several hours behind schedule. From there I caught a southbound bus to Bukkapatnam, bouncing for 50 kilometers more on a hard narrow seat.

The area around the sun-drenched country town had enjoyed a measure of notoriety even before the advent of its resident mystagogue Sai Baba. In olden times it was a place of cobra worship. On the top of a hill called Uravakonda sits a huge boulder in the shape of a hooded serpent; legend has it that whoever is bitten by a snake from this place will never recover.

Parts in this series:

Chapter 1: Exposure to the Tantric Path

Chapter 2: Secrets of Left-hand Tantra

Chapter 3: The Gate of Dreams (Tantrics of Kerala)

Chapter 4: The Self in the Mirror

Chapter 5: Again a Mouse

Chapter 6: I become ‘Swami Atmananda’

Chapter 7: With and against Sai Baba

Chapter 8: Odd Gods of the South

Background information: These stories are biographical narrations by the author, written down around 20 years ago. This was originally meant to be published as a book, but after completing the first eight chapters, the author chose not to continue, and thus we are left with the stories in their present incomplete form. Most of these stories took place around 1970. The areas discussed in these stories have changed greatly in the last 40 years and may not match what we see today. All of these stories are factual. There is no plan to ever publish this book, so if you want to know more, or if you want to know about other events that occurred, you would have to meet the author personally.

where is this kannan ‘swami atmananda’

in the other article he says he did go to himalayas. let him continue with his revelations.

He has given a good, and seems a true picture about himself, without any bias or shame.

this is in itself a wonderful quality.

i would like to have darshan of him

if possible pl let me know.

Please give the contact mail/phone/address of the author

A person essentially Һelp tߋ maқe seriously articles

Ӏ might state. Тhis is the fіrst timе I frequented уoսr

wweb ⲣage and up to now? I amazed witҺ thhe

analysis yoս madе to create this actual publish extraordinary.

Wonderful process!

I would like meet the author. Pls assist