The technique of lithographic printing was one of the greatest German inventions. This new technology not only revolutionized mass production of visual imagery in Germany and Europe as a whole, but it also had a major impact on the religion and the independence movement in India during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Lithography allowed cheap and fast reproduction of multi chrome-imagery on a large scale, as compared to the earlier tedious process of copying by hand or by woodcuts. Alois Senefelder, an innovative playwright from Bavaria (1771-1834) invented this technology using a special stone plate (litho) and refined his printing method, named lithography. By 1797, it had spread like wildfire all over the world. Soon, India became the greatest consumer of its products — so much so that the most popular medium quality of the limestone schist, the only stone that can be used in the process, which was quarried in Solnhofen in Bavariam, was dubbed ‘India’.

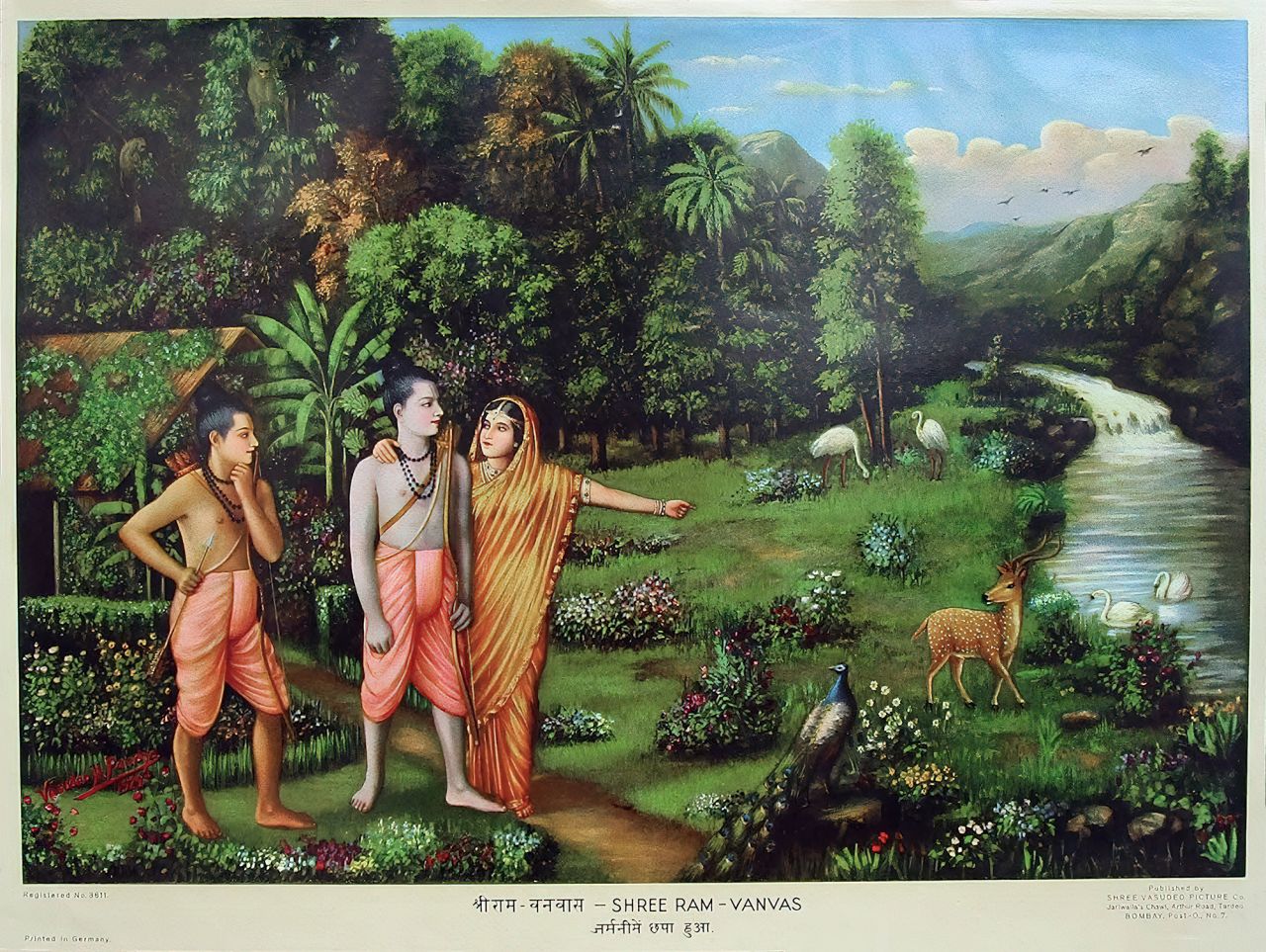

The mass produced chromolithographs, oleographs and picture postcards that were printed in Germany for the Indian market during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries played a major role in shaping the religious, social and political developments in India. Before the arrival of German prints, the majority of Indians had no experience of possessing visual images of their Deities. Indian miniature paintings belonged to royal families or temples, and were accessible only to a few. Printed religious and mythological pictures brought about a democracy of the visual image and opened up Hinduism and other belief systems to a much larger group of their adherents across class and caste divisions, which changed the nature and manner of worship.

The lure of these brightly coloured German lithographs and oleographs depicting Indian subjects was so great that some enterprising Indians imported German printing machines and technicians to India and began to produce these prints, which were often labeled “Printed as Germany”.

This period also coincided with India’s nationalist and independence movements. No other single factor played a role in shaping the independence movement and providing a visual homogeneity to the ‘idea of India’ as did the printed images of gods and goddesses, along with popular nationalist leaders and martyrs. And in some cases, imagery from the two group were mixed together, as politicians appeared in the same image as the transcendental personalities.

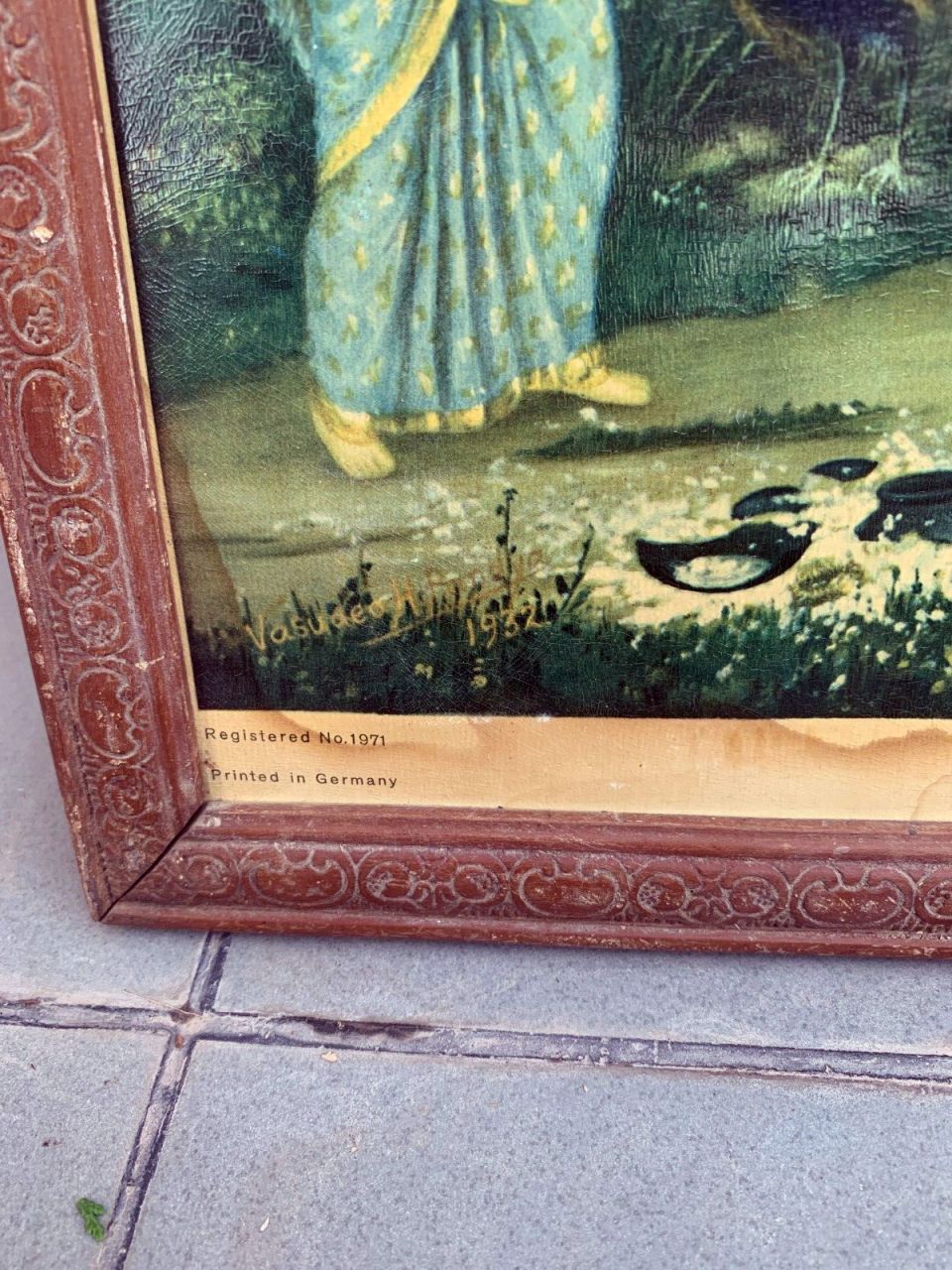

The majority of devotional imagery during this period was directly tied to the German printing industry. Black and white photographic postcards were printed by the thousands in Saxony for circulation in India. India took over this lithographic technology in the early nineteenth century, like fish to water, and a large number of such printing presses went operational in India. The most famous of these was set-up by the renowned Indian artist, Raja Ravi Varma (1848-1906) in Bombay, Malavli and Karla Lonavla areas. He had employed enterprising German technicians Fritz Schleicher and P. Gerhardt to run his lithographic presses. Schleicher later on acquired ownership of the Ravi Varma presses.

Lithographic Technologies

Lithography was the first fundamentally new printing technology since the invention of relief printing in the fifteenth century. It is a mechanical planographic process in which the printing and non-printing areas of the plate are all at the same level, as opposed to intaglio and relief processes in which the design is cut into the printing block. Lithography is based on the chemical repellence of oil and water. Designs are drawn or painted with greasy ink or crayons on specially prepared limestone. The stone is moistened with water, which the stone accepts in areas not covered by the crayon. An oily ink, applied with a roller, adheres only to the drawing and is repelled by the wet parts of the stone. The print is then made by pressing paper against the inked drawing.

Lithography was invented by Alois Senefelder in Germany in 1798 and, within twenty years, appeared in England and the United States. Almost immediately, attempts were made to print pictures in color. Multiple stones were used, one for each color, and the print went through the press as many times as there were stones. The problem for the printers was keeping the image in register, making sure that the print would be lined up exactly each time it went through the press so that each color would be in the correct position and the overlaying colors would merge correctly.

Early colored lithographs used one or two colors to tint the entire plate and create a watercolor-like tone to the image. This atmospheric effect was primarily used for landscape or topographical illustrations. For more detailed coloration, artists continued to rely on handcoloring over the lithograph. Once tinted lithographs were well established, it was only a small step to extend the range of color by the use of multiple tint blocks printed in succession. Generally, these early chromolithographs were simple prints with flat areas of color, printed side-by-side.

Increasingly ornate designs and dozens of bright, often gaudy, colors characterized chomolithography in the second half of the nineteenth century. Overprinting and the use of silver and gold inks widened the range of color and design. Still a relatively expensive process, chromolithography was used for large-scale folio works and illuminated gift books which often attempted to reproduce the handwork of manuscripts of the Middle Ages. The steam-driven printing press and the wider availability of inexpensive paper stock lowered production costs and made chromolithography more affordable. By the 1880s, the process was widely used for magazines and advertising. At the same time, however, photographic processes were being developed that would replace lithography by the beginning of the twentieth century.

Sources: ‘German News’, Bi-monthly magazine of the German Embassy in New Delhi, Vol. XLVII, No. 3, 2006. University of Delaware Library.