Pushpaka Brahmins are a class of Brahmins in Kerala who show attributes of both the Brahmins and Kshatriyas. Hence this caste is generally considered as an intermediate caste between Brahmins and Kshatriyas. They are commonly known as Arddhabrahmanar, i.e. Semi-Brahmins. They carry on the various activities of the temple, though not the actual ceremonies. Pushpakas lived on the income of the temple and were under its care. They are generally clubbed under the Ambalavasi community in Kerala.

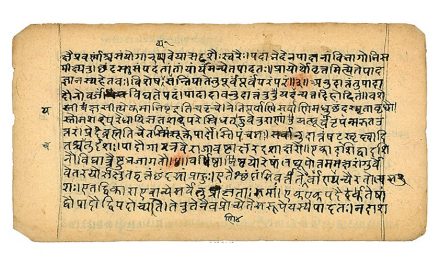

The Pushpakas learn Sanskrit shlokas, mantras etc. and do priestly duties and ceremonies for the lower castes on behalf of the Namboothiri priest. Foreign travellers in Kerala classed the Pushpaka Brahmins (Ambalavasis) with the Foreign Brahmins like Konkanastha Brahmins, Iyers, etc. while making historical records. In fact, Pushpaka Brahmins formed an intermediate class between Brahmins and Kshatriyas.

There are similar Brahmin communities found all over India. The Niyogi Brahmins of Andhra, Chithpaavan Brahmins of Maharashtra, Bhumihars of Bihar, Mohyal of Punjab, Tyagis of West Uttar Pradesh etc. are all Brahmin communities having the same status of Ambalavasis in Kerala.

Subcastes/Surname Variations

Pushpaka Brahmins include various subcastes within itself. They encompasses surnames like Unni, Nambeesan, and Nambidi. However, they use the surname Sharma in common. The surname Nambeesan is used by the Pushpakas in the North and Middle Kerala. Unni is usen Middle and Southern Kerala. The surnames Nambi and Nambidi are generally found in Southern Kerala.

Gotras

Of the various subcastes the Yajñopav?tadh?ri Pushpaka Brahmins (Sacred-thread wearing Pushpaka Brahmins) like Unnis, Nambeesans, M?ttatu etc. belong to the Viswamitra Gotram. They adhere to the ‘Gayatri’ mantra.

The non-threaded Pushpaka Brahmins belong to Kaushika Gotram and adhere to the Panchakshara mantra. However, some of the non-threaded Pushpaka Brahmins claims different Gotras. For example, the Pisharodys claim that they belong to the Vaikuntha Gotram and the Warriers claim that they belong to the Kailasa Gotram, which adheres to the Maha-Namah-Shivaya mantra. This claim is not sustainable, however.

Origin

As per the famous pastimes of Parasurama, the warrior sage Bhargava Rama (Parasurama) is said to have brought a group of Brahmins to Kerala, of which 64 families were allowed to conduct the ceremonies in the temples. They became the Namboothiris. The remaining families of Brahmins became their assistants and were not allowed inside the Sree Kovil or main shrine of the temple. They came to be known as Pushpaka Brahmins, as their work was associated mainly with flowers. Since they resided on the premises of temple, they also came to known as Ambalavasis, meaning Temple-inmates.

The Pushpaka Brahmins lived within the temple premises managing the various affairs (other than the ceremonies in Sree Kovil) of the temple. Their work was socially very respectable.

Services

Pushpaka Brahmins were temple employees but they were not aristocratic, like the Namboodiris. In the past they resided within the temples in their quarters and were sustained by the temple. They were simple people who lived at the benevolence of the temple. Other than their services in the temple, the Ambalavasis were the priests for the lower castes as well. M?ttatu (Muttatu/Moosad), Ilayatu (Elayathu), Nambidi and Nambeesans conducted the various religious sacrifices for the Nairs, though not in the temples, while the Marayars conducted the birth, wedding and death ceremonies of lower Nair subcastes in Travancore. Elayatu is the traditional purohit (priest) of Nayars who conduct the after-death rites for them in Malabar.

Art Forms

The contribution of Pushpaka Brahmins of Kerala to the cultural heritage of India in the fields of art is substantial in every sense. Ambalavasis have, through the centuries, developed several art forms of a religious or quasi-religious character. The major art forms developed by the Ambalavasis are as follows. They developed in the atmosphere of temples, which have long been centres of great cultural activity.

Sopanam is a form of Indian classical music developed in the temples of Kerala in the wake of the increasing popularity of the Jayadeva’s ‘Gita Govinda’ or ‘Ashtapathi’. Sopanasangitham, a form of worship of Sri Sri Radha Krsna, is sung by the side of the steps (Sopanam) of Temple to the accompaniment of a drum called ‘Idakka’. The Sopanasangitam in its traditional form is seen at its best among the Marars and Poduvals, who were hereditary Ambalavasi Ardha brahmanas (Semi Brahmins) engaged to do the same.

Guru Padma Shri Mani Madhava Chakyar performing Chakyar Koothu

Chakyar Koothu is a performing art form in the form of a mono act, or the traditional equivalent of a stand-up comic act. However, unlike the stand-up comic, the performer has a wider leeway in that he can heckle the audience.

“Koothu” means dance, which is a misnomer in this case, since there is minimal choreography involved in this art form. Facial expressions are very important, though. Traditionally it was performed inside a temple, with the performer beginning with a prayer to the Deity of the temple. He then goes on to narrate a verse in Sanskrit before explaining it in the vernacular Malayalam. The narration that follows touches upon various current events and societal factors with great wit and humor.

Ottamthullal is a type of performing art that is also known as the “poor mans Kathakali”. Ottamthullal was created by the Malayali poet Kunchan Nambiar as an alternative to the Chakyar koothu, as a protest against the prevalent socio-political structure and prejudices of the region. In Ottamthullal, a single actor wears colorful costumes, while reciting thullal (dance songs), all the while acting and dancing.

The art form is very satirical in nature, and the ability and freedom of the artist to invent and incorporate the humour and incidental satire makes this art form more popular among the common man. Unlike Kathakali, the language is pretty simple, Malayalam and very rhythmic in nature.

Guru Mani Madhava Chakyar and his troop performing Thoranayudham koodiyattam

Koodiyattam or Kutiyattam is a form of theatre traditionally performed in Sanskrit. It is believed to be at least two thousand years old, and is officially recognised by UNESCO as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

Tayattu was a traditional dance form performed by the peoples of Unni and Nambiar castes in Kerala. The performance has three parts – preparation of the kalam (Kalamezhuthu), singing songs in praise of Bhadrakali, and the performance of the dance. Kalamezhuthu is done during the day using natural coloured powders on the floor. An elaborate picture of Bhadrakali is normally made. The singing of the songs take place after the Kalamezhuthu is finished in front of it and may last up to three hours.

Brahmanippattu is a type of domestic devotional offering performed usually in connection with marriages. Women of Pushpaka Brahmin (Ambalavasi) caste Hindus called Brahmanis or Pushpinis alone are entitled to do it.

In the dance, the women stand round a decorated stool on which some symbolic representation of Bhagavathy is placed. They then sing devotional songs to the rhythm of the beating of bronze plates. These songs were sung mainly for the blessings of Goddess Durga. Gradually the songs ascend in pitch and the women dance in ecstasy.

Panchavadyam performance during a festival in Kerala

Panchavadyam meaning an orchestra of five instruments. It originates from Kerala and is another temple associated art form. The orchestra (pictured above) is composed of five percussion instruments: Timila, Maddalam , Edakka, Elathalam and a wind instrument Kompu.

Recent History

Up until 1865 in erala, all the land was under the Namboodiri and Nair landlords. The act passed by the British Dewan of Travancore, Colonel Munro, in 1865 called the Pattom Act, ended this tenantship and all the lands held by a family became theirs. Following this, when Sanketams or regions where the Namboodiris autonomously ruled, were banned, the Ambalavasis who were sustained by the temple gained land as well. All the land owned by the temple was divided among the Ambalavasi families living in the premises. Since then, the Ambalavasis came into their own in the various scenes of social and political life in Kerala.