The local Gujarati communities are renowned for their commercial success and as published accounts relate, their origins in Fiji could be traced to Porbander in India. Located on the Kathiawar peninsula, the coastal town is more famously known as the birth place of Indian activist and spiritual leader Mohandas Gandhi. In a closer-to-home context though, this was also from where the plethora key traders in Fiji sprang.

Early merchants

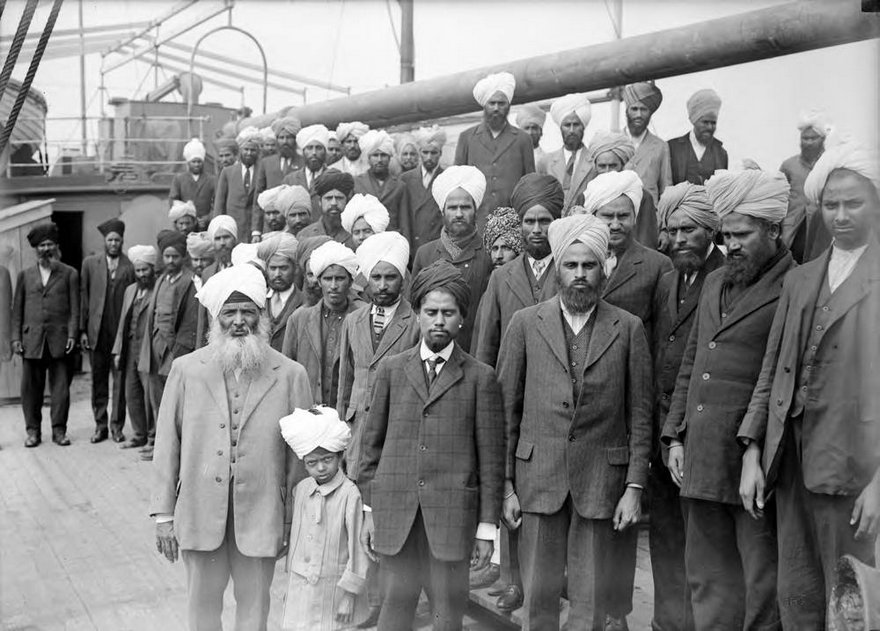

Expanding trade routes and commercial prospects in the earlier part of the last century led to a wave of merchants, traders and craftsmen sweeping into Fiji from India and China. Many founded large families, with some descendants still practising the traditional craft of these entrepreneurial ancestors.

As noted in Kenneth Gillion’s book, Fiji’s Indian Migrants, the first of this lot were Virjee Narshi and Choonilal Gangjee, a pair of jewellers who migrated from Natal in 1906 after hearing of Fiji from Indians who had been contracted here as indentured labourers.

Their arrival was followed by more jewellers from Porbander, Jamnagar and Jetalsar, as well as goldsmiths, silversmiths and tailors, including Geroge Nanco.

“The peak of this ‘free’ immigration (as it was called at the time) was not reached until the 1920s, but perhaps two or three thousand arrived before 1920,” Gillion noted in his publication.

From 1901 to 1907, numbers steadily rose from at least 100 to 1000, with 250 immigrants arriving annually from India by 1911.

The immigrant peak of the 1920s included Punjabi farmers, Gujarati craftsmen and traders, religious teachers, missionaries and lawyers.

They also included relatives of Fiji settlers, and returning travellers who had visited India with their free return passages.

“They came to trade, bringing merchandise with them, or to be priests, or to earn high wages,” Gillion noted, adding that the Immigration department had also tried to coerce able-bodied free immigrants into indentured labourer by offering refunds of their passage fare.

“But very few were willing to give up their freedom or to become field labourers at all. Instead, they became labourers in the town, storekeepers or hawkers, and eventually leased land.”

Punjabi free immigrants also arrived as early as 1904 from Noumea, New Caledonia, and in 1905, when New Zealand’s Union Steam Ship Company started a three-monthly service from Calcutta to Auckland that had a connecting service to Suva.

Published accounts noted that of the 600 businesses registered in Fiji between 1924 and 1945, 300 trader licences were held by Gujaratis.

Makanji H Raniga

Gujaratis who settled in Fiji often achieve commercial success through traditional vocations as traders and merchants, though the path was often fraught with poverty and the heartbreak of detachment from relatives in India.

Those who chose to make the sacrifice and jump on a rickety ship in Calcutta included Makanji Harjiwan Raniga, who arrived in Fiji in 1932.

“When my father came to Fiji, he first went to Suva and then on to Labasa, before moving to Nadi,” noted son, Laxmi Chand Raniga, the director of the Nadi-based Raniga Jewellers.

It was in Labasa where he was known as “Makan Taxi”.

Taxi services weren’t commonplace in the decade, but as someone who always seemed ahead of his time, it was a vocation Makanji jumped into anyway.

“He was from Bhaunagar in the state of Gujarat and came on the ship with other figures like Punja, Morarji and Chagan Lal.”

The late patriarch was born in Barwala, Bhavnagar in Saurashtra, Gujarat, likely around 1898, and had a younger sister, Jamku Ben.

Family accounts noted that a 1921 plague forced the family to relocate to Lusara, where both their parents succumbed to the outbreak.

“They took shelter in the Maal Bapa Mandir, Manekvada and even after the danger of the plague, both siblings continued to reside in Lusara for a further 11-years.”

After arranging his younger sister’s marriage, Makanji boarded a Fiji-bound ship at the Port of Calcutta and like other passengers, endured tough and sanitary conditions.

He had a brief spell as a labourer before moving to Labasa, where he began a handicraft and jewellery business.

“However, when the business did not do well, he bought a car and registered it as a taxi. He drove the taxi and was nicknamed Makan Taxi,” the family recounted.

An influx of American soldiers during the World War II reinstated his handicraft business, as there was a demand for jewellery, and this time around, Makanji found greater success with his business in Suva.

“My father also worked for Makanji K Pala at his grocery store along Marks St in Suva and was in the capital for about ten to eleven years,” Laxmi Raniga added.

Makanji eventually settled in Nadi, which in the ’40s was gradually changing.

Swami Vivekananda High School (now College) had opened its doors in 1949, the first non-Christian and non-government secondary school in Fiji.

As noted in Brij Lal’s publication, In the Eye of the Storm: Jai Ram Reddy and the Politics of Post-Colonial Fiji, this was nothing short of a revolutionary act of defiance of colonial authorities, as it had forged ahead despite opposition and objections to the prospects of its school leavers.

The town’s rapid development would also because of its use as a landing and dispersal point for the US Air Force against Japanese targets during the World War I, and formative works on what is now the Nadi International Airport.

Family life

In 1941, Makanji married Narbada Ben, younger sister of Nadi’s first mayor, former National Federation Party executive and Parliamentarian, Hargovind Mavji (HM) Lodhia.

The couple moved to Momi, outside Nadi, before financial hardships led to several relocations around Nadi and Lautoka.

Their sons, Suresh, Rajendra, Girdharlal, Laxmi, Dinesh and Jayendra would all bear the middle name Makanji. Their sisters were Muktala Madan, Sadar Bhindi, Shakunpala Vasram and Praveena Meghji, whose families would also draw economic success through their own ventures.

Laxmi Raniga remembers the business activities of his father, whose skills trickled down to his children. He was part of an ambitious wave of migrants and was determined to provide a find new existence under foreign skies.

“He was a goldsmith himself. After he left Labasa he ran a small grocery shop at Tavakubu, Lautoka and in Narewa and Sabeto, Nadi, and several other places,” he said.

In 1965 Makanji Raniga settled at Lodhia St, Nadi Town and was finally able to make a return trip to India with his wife in 1970, to rekindle ties.

He passed away in 1980, though his family retains a degree of commercial success in his adopted town and beyond.

Hats off to the writer for his painstaking efforts. Very inspiring one. Lesson learned — There is no substitute for hard work , sincerity and bold , timely actions , in in our life.

This article is inspiring indeed. Thank you to the writer. I also feel that more of this type to be broadcast as often and as much as possible. The history of our Indian forefathers deserves to be celebrated. Further to this, I’m eager and I’m sure many others are,to read about the History of Indians in South Africa.