Dharma is a very familiar term in Hindu epics, purāṇas and other literary works that highlight the ideal ways of human life. We find the term in the major Upaniṣads and Bhagavad Gīta also, used in varying senses like virtue, righteousness and religious duties. Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad says in verse 1.4.14 that Dharma is instrumental in making the world flourish; in the beginning, it was created on finding that world was not flourishing through the earlier creations of four Varṇas.

Taittirīya Upaniṣad (1.11.1) insists that Dharma should be strictly observed in life, without fail. In Chāndogya 2.23.1 three types of Dharma (religious duties) are prescribed. Thus scriptures assign great importance to Dharma. Nevertheless, this term is not seen defined anywhere exhaustively. If Dharma exercises so great an influence in human life as indicated, we should definitely find out what it exactly consists of. Let us here make an enquiry for the purpose.

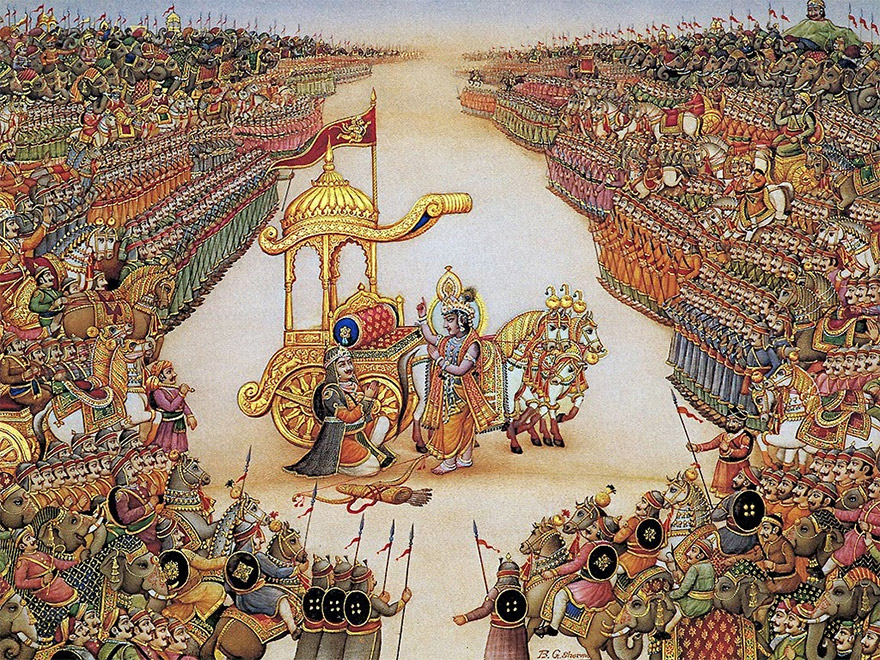

In the first chapter of Gīta on ‘Despondency of Arjuna’ (अर्जुन विषाद योग – Arjuna viṣāda yoga) Arjuna laments about the probable breach of Dharma that he may incur if he kills his close relatives, preceptors and friends in the battle. At the moment of commencing the fight, Arjuna became grief-stricken and confused on seeing his own relatives, Bhīṣma in particular and also Gurus, on the opposite side. The very thought of killing them in battle was excruciating for him. He was ready to forsake anything including his life for their good. He makes his own evaluation on what to do or not to do at the moment, weighing all the options on the touchstone of Dharma.

Arjuna’s thoughts proceeded on these lines: ‘I am not delighted in killing the Sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra since they are my relatives; slaying one’s own people is a sin. Even if they don’t realise what will happen if one’s own clan is ruined, we are well aware of it. When the clan is ruined, its age-old Dharma will decline and Adharma will take its place. Adharma will cause the women of the clan to be immoral, which in turn will result in varṇasaṅkara (mixing of varṇas). As a result, the whole clan will be destined to hell; forefathers will be deprived of the offering of piṇḍa and water and consequently, they also will fall into hell. Varṇasaṅkara will also cause erosion of caste-dharma(s). With all the Dharmas lost in this way, what awaits us is permanent lodging in the hell. It is pity that we have resolved to commit such a great sin by killing our own people, simply for wresting the throne. It would be better for us if the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra kill us when we are not fighting and without arms.’ Deeply moved by these thoughts Arjuna gave up his arms and sat down in the chariot with great sorrow.

Thus, Arjuna’s thoughts are singularly concentrated on Dharma and its possible violation in his actions. But what does he understand about Dharma? To him, killing one’s own kinsmen is not Dharma under any circumstance. He fears that such killing will ruin their clan and its Dharma. Varṇasaṅkara will follow, which in turn will result in erosion of caste-dharma(s). Finally, the entire clan will go to hell. In short, he thinks that killing relatives initiates a series of grave violations of Dharma. He also thinks that each clan and each caste have their own well-defined Dharma.

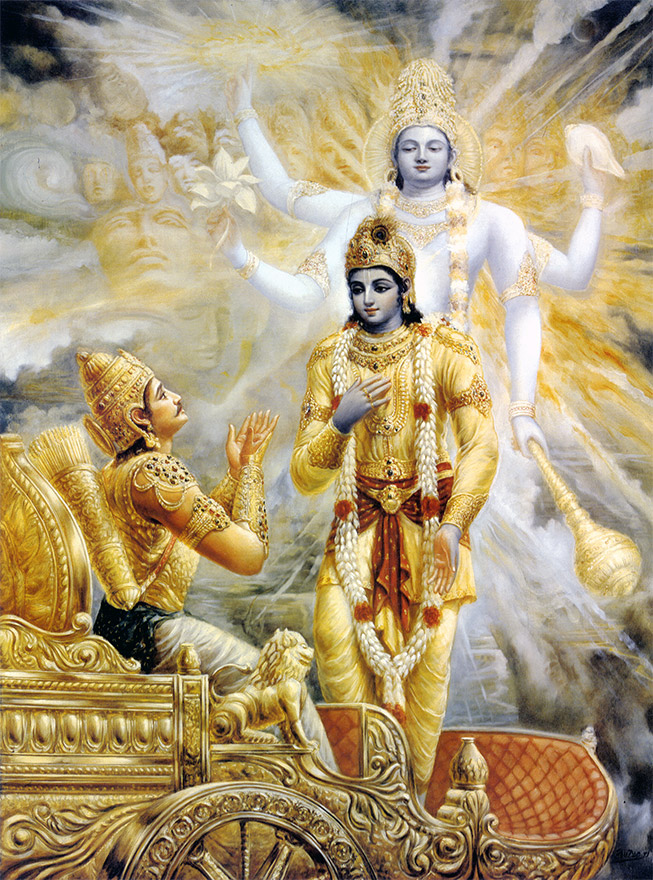

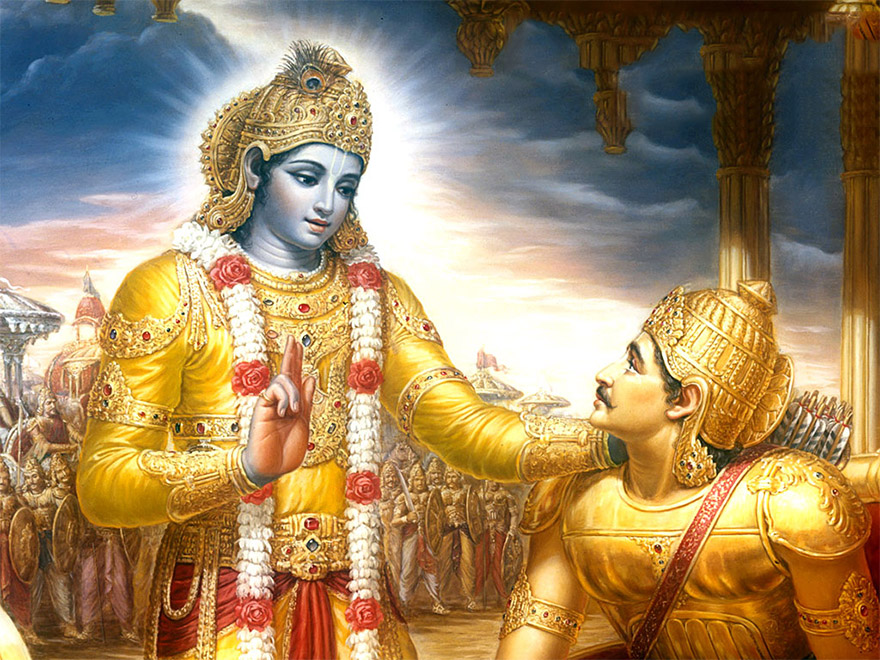

When someone refuses to arrogate material wealth through killing own relatives, he would normally be hailed as an ideal person inspired by the highest sense of Dharma. As such, Arjuna deserves acclaim and encouragement for his concern about Dharma and for his well-matched speech and action. But, on the contrary, Lord Kṛṣṇa condemns him, depicting his despondency as mere weakness; He also indicts Arjuna, charging that his actions are totally unbecoming of a man of his stature in the given context. This denunciation of what apparently is a great act of Dharma indicates that Arjuna’s concept of Dharma is not acceptable. Realising that what Arjuna apprehends is really the strike of sin allegedly involved in killing relatives, Kṛṣṇa commences a series of detailed instructions on how to do Karma without being smeared by sin. These instructions constitute the revered text of Bhagavad Gīta.

Kṛṣṇa’s chiding of Arjuna’s concept of Dharma and His advice on worry-free performance of Karma give some clues about what Dharma actually is. No action, however cruel that may appear to be, can be condemned as sin, outright. Similarly, no action, however esteemed it may appear to be, can be prima facie branded as Dharma. The criterion for classifying actions as Dharma or sin is very sophisticated; it depends upon the way of doing the action, the purpose served, the intention of the doer, etc. Yes, the basic scriptural texts of Hindus do not attempt an exhaustive classification of actions into Dharma and Adharma (sin); nor is there any blanket sanction or restriction for any action. Our day-to-day experience vindicates this stand. Killing a person is normally considered a punishable act. But, when a soldier kills the enemy, it is hailed as a brave act. Similarly, to cause a wound on another person’s body is considered objectionable. But, the same act is permissible when a surgeon undertakes it as part of a clinical operation. That means, we cannot classify the mere act of killing or wounding as expressly Dharma or Adharma.

In Bhagavad Gīta, while refusing to fight, Arjuna forgot the atrocities and heinous acts of Duryodhana and his cronies inflicted on the Pāṇḍavas in the past. Meek submission to such atrocious acts and injustices would amount to their tacit endorsement. Reluctance to react against Adharma is tantamount to Adharma, as that would abet its repetition and perpetuation. Acts of Adharma is to be fought out by any means; if use of force is required we have to resort to it. Arjuna’s fear of breach of Dharma was therefore out of place. In the current stream of social order also, this notion is already in acceptance. For example, an instance can be cited from our criminal laws. The method of arresting described in Cr.P.C of India provides for use of force if there is no submission to custody by word or touch; if the offence is punishable with death or life imprisonment, arrest is to be made even by resorting to the death of the culprit.

Let us now make an attempt to further unveil the true nature of Dharma through the reverse route of Adharma or Pāpa (sin). What is Pāpa? It is any action that attracts a punishment. Why does it attract punishment? Because it involves some wrong, done to somebody. What wrong can a person possibly do to somebody? Many, innumerable. These innumerable numbers can be classified into three categories; first, that affects the right to exist; second, that curtails one’s right to self-expression and third, that obstructs one’s happiness. These three, viz. existence, expression and happiness, are very important. Expression involves knowledge also. For, without knowledge, expression is void and reversely, knowledge inspires expression. Knowledge and expression sustain mutually in an inseparable combination.

All actions of all people of all epochs are motivated, without exception, by the trio of existence, expression and happiness, either jointly or severally. That means, every action is done in furtherance of either existence or expression (+knowledge) or happiness (enjoyment). Therefore, Pāpa is to be understood as any action that impedes existence-expression-happiness trio of others. Ancient Hindu Sages abstracted and understood this trio as SAT-CIT-ĀNANDA (सत्-चित्-आनन्द) and called it Ātmā (आत्मा). They also postulated that Ātmā is the origin and ruler of all. With this understanding about Ātmā, Pāpa can be deduced as that which negates Ātmā. Conversely, Dharma is that which is in conformity with Ātmā. In other words, Dharma represents any action that contributes to the existence-expression-happiness of others. The word ‘others’ include every other being and, vicariously, means the whole.

This concept of whole is very important. For, existence of the whole is a pre-requisite for the existence of the individual members. When the whole is destroyed, individuals will not be there anymore. Therefore, that which serves only a few at the cost of others is not Dharma. This does not mean all are equally served; it is to be ensured that the whole as a whole is protected. In this context, let us recall a prayer in the peace invocation of Sāmavedīya Upanishads, ‘May I never deny Brahma’ (माहं ब्रह्म निराकुर्याम् – māhaṃ brahma nirākuryām). The prayer warns against ‘thinking to be separate or different from Brahma’ when one furthers his interests, which means that he should take care of others’ interests also. This endorses the importance of ‘the whole’ highlighted above.

Before proceeding further, let us now consider how Pāpa attracts punishment as mentioned above. We know that Pāpa represents Karma that is not in conformity with the ultimate principle of existence-expression-happiness. It is a fact that the doer of Pāpa also is ruled by this inner principle. Pāpa occurs when he does not pay heed to the dictates of this ruler within himself. But the ultimate principle is inviolable and indestructible; so it retaliates and intervenes to reassert itself. This creates conflict in his mind and as a result, his peace and tranquillity are upset. This in turn takes away his power of judgment that ultimately leads to his total ruin. The re-assertion by the ultimate principle happens naturally, whenever it becomes essential. This process is what is described in Gīta 4.8 as ‘saṃbhavāmi yuge yuge’.

Now that the essence of Dharma is known, what remains to be probed is how it happens to be Sanātana (eternal). We have seen that every action of every being is motivated by the urge for either self-existence or self-expression or self-happiness. We have also seen that while furthering such individual urge, it is to be ensured that the existence-expression-happiness of the whole is not infringed, since individual existence is not possible without the whole. Every individual action for existence-expression-happiness has to maintain a balance with those of the whole. In order to ensure this balancing, which is essential for universal existence, formulation of certain codes of conduct becomes inevitable. Such codes designed for regulating the performance of Karma by individuals are known as ethical laws and they define human virtues, morals, principles and conscience. These laws have been there in every epoch of human history and they constitute the essence of judicial system of the corresponding periods.

Peaceful co-existence is impossible in the absence of such regulatory edicts. In spite of the different forms these laws take in different ages of history, the underlying objective has always been the same, which is nothing but ensuring conformity of Karma with SAT-CIT-ĀNANDA. Because of the presence of this unity of essence beyond spatial and temporal limitations, these laws are called eternal. Hindu scriptures call them the Sanātana Dharma. Some ignorant ones often scoff at the word ‘Sanātana’ (सनातन – eternal) saying that there is nothing eternal in the universe. They are of the opinion that values of each epoch are different from those of the others. But, whatever be these differences, it could be seen in ultimate analysis that all apparently different values of various epochs emanate from the exclusive objective of conformity of Karma with ‘SAT-CIT-ĀNANDA’ and that the differences owe their existence to the level of understanding of the ultimate reality in that epoch.

Even if we know that Dharma is that which is in conformity with ‘SAT-CIT-ĀNANDA’, it may be difficult for us to confine our actions to Dharma. This is because of the inability to discern what exactly conforms to ‘SAT-CIT-ĀNANDA’. Gīta says in 4.16 that even the wise people are confused in choosing the right action. This confusion was the reason for Arjuna’s despondency at the beginning of the war. Naturally, Gīta is all about how Karma can be performed without being smeared by Pāpa. It may be seen that Hinduism totally rejects the idea that God dictates the choice of Karma and the manner of its execution by us. Such determinism is not recognised by the Hindu Philosophy, wherein it is declared that the Ātmā is only a witness; all actions are done because of the Guṇa(s) (Śvetāśvatara 6.11 and Gīta 3.27, 13.29, 14.19 & 18.16).

In this world the only thing in which we have a free will is the choice of our Karma (karmaṇyevādhikaraste – Gīta 2.47). All the remaining things are not ours and we have no right over them (Īśa 1 & 2). Gīta also says that the Lord never assigns any duty upon anybody or grants the results of any action to anybody (5.14). Nor does He recognise any Karma as either virtuous or sinful (5.15). Therefore, our Karma is our own responsibility and we can never absolve of it with any external grace. When the circumstances necessitate the performance of any particular Karma, it is our choice whether to do or not to do it and also how to do it.

In lieu of choosing a Karma, Gīta puts forth two important options, namely, 1. Sacrifice the results of the Karma for the benefit of the whole, which act is known as Yajña (यज्ञ – sacrifice; Yajña is Karma in which results are sacrificed for the benefit of all) (Gīta 3.9); and 2. Give up all attachments and also remain equanimous to the outcome of the Karma, be it favourable or otherwise (Gīta 2.48). Both are same ultimately, since, without giving up attachment, sacrificing the results is not possible. The entire preaching in Gīta consists in repeated efforts to inculcate these two options in the mind of Arjuna, together with matters ancillary thereto. At last, winding up the instructions, Kṛṣṇa exhorts Arjuna to expel from his mind all that he considers as Dharma and then concentrate on His teachings only, so that he will be relieved from all Pāpas. Please see below the climaxing advice contained in verse 18.66:

सर्वधर्मान् परित्यज्य मामेकं शरणं व्रज |

अहं त्वा सर्व पापेभ्यो मोक्षयिष्यामि मा शुचः || 18.66 ||

(sarvadharmān parityajya māmekaṃ śaraṇaṃ vraja,

ahaṃ tvā sarva pāpebhyo mokṣayiṣyāmi mā śucaḥ.)

This verse is seen interpreted in different ways by Ācāryas and scholars. Mostly, the interpretations assign the meaning ‘all righteous deeds’ to ‘sarvadharmān’. Ādi Śaṅkara interpreted the phrase ‘sarvadharmān parityajya’ as an advice to give up all Dharma and Adharma together, since, in his opinion, Naiṣkarmya (नैष्कर्म्य) is intended to be taught here. (Naiṣkarmya is a state of mind wherein, due to absence of desire, there is no inner urge to undertake any Karma). But these interpretations do not conform to the message of Gīta, which does not relieve anybody from performing Karma, but only prescribes the ways to stay away from being smeared. Lord Kṛṣṇa says in Gīta 3.22 that He too is always engaged in Karma, though there is nothing to gain personally. This obligation to perform Karma is in full agreement with the instruction in Mantra 2 of Īśa Upaniṣad, which holds that only by doing Karma one should aspire for living a full life.

Moreover, how can Gīta which calls upon us to sacrifice the results of our Karma for the benefit of the whole, make an advice to give up all ‘righteous deeds’? Is it that Karma performed in this way is not a ‘righteous deed’? It cannot be so. Again Gita asserts in verse 3.4 that Naiṣkarmya cannot be attained by simply abstaining from Karma. This utterly disproves the contention of the Ācārya. Such interpretations might be the result of not giving due importance to the contents of chapter 1 of Gīta, wherein Arjuna is presented as deeply worried about what he understands as Dharma. The concluding verse of 18.66 directly connects to the opening topic ‘despondency of Arjuna’ and advises him to set aside all that causes worry, which is precisely his own version of Dharma. Kṛṣṇa disapproves Arjuna’s perceptions about Dharma and therefore asks him to abandon them all.

We may wind up our discussions by concluding thus: Dharma is that which conforms to the ultimate principle of and in order to ensure this conformity in our Karma, we must either sacrifice the results thereof or perform Karma without attachment and without considering whether the result is positive or negative. Dharma is Sanātana as it does not change by the change of time or place; in all epochs and all places, it is invariably Dharma that sustains and supports everything. Hinduism is the religion of Dharma which is Sanātana. The supreme spiritual accomplishment envisaged in Hinduism is attainment to the ultimate principle of SAT-CIT-ĀNANDA (ie. Ātmā) to which Dharma owes its conformity.

(Author: Karthikeyan Sreedharan)

The right concept of dharma can be seen in the manusmriti. the manusmriti is the Dharma Shastra. It says Vedo akhilo dharma mulam that is the source of all knowledge of dharma is the Veda.

Commentary by Shri Karthikeyan Sreedharan pleads to simplification of Dharama and Sanatan philosophies of Hinduism. Explained in such a simple but comprehensive expressions the author has done a great service to mankind. Gods be with him.

PS where can I get a copy please.

Namaskar all readers ! Into this civilizational brilliance how and when did plastic enter the Indian food chain…now apparently distributed as an ingredient in cow 🐮 milk? Has progress brought plastic with it to a cow reverent tradition and are we finding it difficult to resolve the contradiction of keeping the two together while keeping them apart? India and India Divine could do well to deal with such ironies in our lives 🍴

An innovative intellectual effort in examining the meaning of DHARMA. Logical and thought provoking.

I think synthesis of existing material about any issue is a characteristic of the thinking Indian mind.This is the first step a scientist makes.

Based on my limited studies I have the following hypothesis,mostly based on my understanding of the lectures of J Krishnamurty and Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras on what can make one understand the truth or the “SAT” and thereby the wisdom of what is dharma and what is Adharma .

Through an intense examination of the thoughts arising in one’s mind one can observe the entire network inside our brain -the construction of an “I”, the origins of “RAG” and “DVESHA” .This is what is explained in the Sutras in the first chapter by Patanjali and also by Jiddu krishnamurti.

The mind freed of all past clutter attains a clarity that helps one see every happening, at any moment, in its fulness and therefore the response is also complete and appropriate.

There is need of any formula for living because the mind has seen the truth or the SAT- the interconnected world, rather the universe.When the “CHIT”( mind) is living in that truth it full of ANAND(bLISS).

If one examines the discoveries made by physicists about the Origins of the Universe with the “BIG BANG” , it reinforces the truth(SAT) that everything in this universe has one origin. Birth of an animal or plant is just an organised collection of atoms in which life springs because of a certain combination. The rest of the non living matter of the universe is also made up of atoms. Dharma means to respect this unity and live and work with that truth in mind.

The conflicts between men are because of the lack of this vision.

An examination of one’s own mind ,helped by others who are similarly engaged, is the only way to gain wisdom of living a life in truth”SAT”.

The more we comment on the Gita, the more confusion is caused.

The message of the Gita is very simple, and straight.

The scripture opens with Dhritarashtra referring to Dharmakshetra. Arjuna sets the ball rolling by saying he is confused about Dharma and seeking instructions for Sreyas. Krishna concludes by asking him to abandon all Dharmas and take refuge in Him. Where is confusion here?

Arjuna is not a nut. He is a Kuru prince and appropriately educated, on traditional lines. He is endowed with Daiva sampat, according to the Lord.There are conflicting elements in traditional dharma. [ Your dharma about satwik food may be violated by taking medicine containing garlic according to medical dharma.] As a Kshatriya prince, Arjuna knows his normal dharma, but he is up here against his venerable elders and teachers. Hence the confusion, due to fear of committing sin.

Krishna concludes by asking him to surrender, and hang all dharmas! He will free him from all sins. This is very straight!

Out of 700 verses of the Gita, the Lord speaks 569 verses. Of these, more than 140 are straight on the theme of Bhakti- ananya bhakti. On no other topic has He spoken so extensively. And wherever He mentions Bhakti, He uses supreme epithets like Raja vidya, Raja guhyam, Mae paramam vacha, guhyat guhya taram. guhya tamam, guhya taram, etc. Those who do not believe in this will not reach Him. (9.3.)

Then why does Bhagavan talk about all those other things?

– because it is all part of the traditional knowledge which Arjuna has acquired, and we can only begin from what we know.

– because sankhya and yoga are old systems (pura prokta) which have to be ended or mended. Here the Lord mends them by-

a) converting karma into yoga and yajna, performed as Bhagavan’s aradhana, and without attachment to fruits, by offering everything to the Lord.

b) by showing that real sankhya (jnana) is to know that Bhagavan is the Lord of prakriti and is not bound by it. To know that Bhagavan is all this, and he is Supreme ( yukta aasita mat para ) is real jnana ( and not the empty and endless speculations about Jiva, jagat, Iswara.)

– an embodied being cannot avoid or abandon karma totally. So he has to avoid kamya karma, and only perform niyatam karma, karyam karma = obligatory duties. And surrender the fruits to the Lord.

Thus it is surrender to Bhagavan which is the real Dharma advocated by Bhagavan Himself. All other dharmas will have to go. Absolute surrender to the Lord is the only Dharma we need!

Why think of all the old things and confuse ourselves in the present age?

Kali kalmasha chittanam, papa dravya jeevinaam

Vidi karma viheenaanaam, gatir Govinda kirtanam.

This is reinforced in the Vishnu Sahasra Nama. There, after listening to all dharmas ( srutva dharman aseshena ) Yudhishthira asks Bhishma about one supreme dharma ( ko dharma sarva dharmanam bhavata: parmo mata: )And Bhishma tells him the thousand names of Bhagavan as the supreme dharma. This happened in the presence of Bhagavan!

So for us, surrender to Bhagavan is the only dharma in this age!

We salute all acharyas from a distance, but for us Lord Krishna is Gurur Gariyan!

[I can cite chapter and verse for all statements made here but that will make this reply very long.]

Basic things first. Dharma comes last. What is a human body is made up of and how the “I” entity works in all without realising all are “I”s. Then proceed to realise the I. Matter closed. That is our Dharma to be aware of “I”

The verse “sarva dharman parityajya …. , 18.66 of the Geeta need not be seen as contradictory to earlier statements for keeping up dharma. The Geeta prescribes 4 ways for liberation or happiness, or Sat-Chit-Ananda, viz., Karma (working according to one’s prescribed duty, Swa dharma karma), Jnana, (the way wisdom), Abhyasa yoga (physical exercises for controlling the mind), and the fourth, Bhakti, devotion, (complete surrender to a Guru or deity).

The verse 66 of chapter 18 of the Geeta “sarva dharman parityaja maam ekam saranam vraja” is the way of Bhakti, devotion. Dharma is relevant while doing Karma. However, all the four ways lead to liberation or Sat-chit-ananda.

Kanchii Mahaperiyava’s speeches are lucid and of great value of every one of US.

Sanataana Dharma, the practice of eternal dharma of the most ancient vedic tenants for individuals to perfect oneself by resorting to the Karmanustana to get rid of the sins of earlier births and to ward of present accumulations are the main principles to be noted.Purity in mind and thought, strive for universal happiness, consider all creations are He HIMSELF embodied in the Dharmic tenants are only to attain the Paramananda- Ulimate for no rebirth.

Thanks for thought provoking explanation and hope to get some more for self realisation.

Holy Mother so many interesting comments and one of my favorite articles

sophia nyc

The author Karthikeyan Sridharan has beautifully and comprehensively defined dharma based on our ancient scriptures. It is a very abstract topic ,to bring a clarity in such topic requires in depth knowledge and conviction. This article clearly depicts both.

God’s grace will be with him so that he continues to contribute such article for the benefit of readers .

L Viswanathan

I keep these lessons on my mobile phone vide my emails. In my leassure hours which are very hard for me otherwise, I read these articles. They give me peace and solace.

A very useful article! Hope analyses like these bring clarity in all in these times of illusion – when mere numbers in form of statistics and people’s support to form a simple majority are used easily to justify ‘alterations’ to Dharma or to label a right way to a wrong one, or portraying a virtue as a weakness.

Dear Sir

My hearty Greeting for Independence Day first.

In the context of ‘Understanding Sanatana Dharma’ article, can anyone of the learned throw some light on my rather naive queries below? Thankyou.

1). Why is war and the fighting instinct almost an ‘inbuilt’ accepted feature in Hindu religion – that we have a raajasic guna and a warrior kshatriya class given a “license to kill” to protect his stakeholders and Lord Brahma the lord of creation Himself personifies this fighting via Rajasic guna.

2). Why were the powerful Hindu Gods mostly silent during a thousand years of Indian slavery by foreign invasions?

3). What are our Hindu Gods’ expectations in the highly globalized world today? Are all gods of all world religions talking to each another these days somewhere up? Thanks.

Dear Sir

Good day

You are extracting our old history and bringing in frond of NEW HUMANISM, which may very very good.

Present most all the part of “Pregati” one by one convert in to human life which may very bad in the earth those who are living now.

Promotion- Present we are not seeing on earth so many different types of Animals, trees, flying birds, fruits, vegitables and so on

Also Old humanism was not good qualified on each other were living in the earth just like now example “SUNNI/ SHAIK and opposite SHIA” in the Muslim divine.

I am to answer the ‘naive’ queries of Sri. Bharat Kumar. His first question is: why fighting instinct is an inbuilt feature of Hindu religion? I think this question is ill-founded. Hindu religion is not for fighting and ruining. But, it calls upon to fight against Adharma, even resorting to use of force. Hindus are comparatively a calm and peace-loving people in the world. History testifies to this fact.

His second question is regarding the silence of Hindu Gods during thousand years of slavery in India. Hindus have only one God or Isvara and that is Atman. It is the God of all, it pervades the entire universe and also is the energizing force in each and every individual. It is not in human form, but is formless. So, when in trouble we have to act with our body and mind invoking the divine energy within us. All other gods that Hindus worship are simply human imaginations descended down through generations of tradition. They have nothing to do with the ultimate scriptures of Hinduism. We worship those gods for realising selfish material gains only. True devotion in Hinduism is renunciation of cravings (Kaama).

The third question is regarding dialogues between gods of various religions. There is only one God or Isvara, as stated above. So no dialogue problem arises. According to Upanishads, the principle of Isvara is existence-consciousness-bliss. All beings are always acting under the influence of this principle, ie. for existence, self expression and happiness. That’s all.

How Sanatana Dharma came to be replaced by Varnasrama Dharma which divided us; did Krishna really say “I did it?”. Was it not a conspiracy? In the name of Gunas Sanatana Dharma did not divide people but why Varnasrama Dharma did it. Disunity resulted in foreign forces ruling us for nearly thousand years. Satva Guna was most suited for spiritual life and the Rishis followed that. Arjuna was rajasic by nature and Krishna talks to him about soul, realizing true self and the different paths. OK If God had created unequal Varnasrama Dharma why it languished. Our Constitution is based on Sanatana Dharma – equality for all and its vision is a casteless classless society. Gita has many contradictions or hidden meanings in some places. Will you please explain this contradiction?

Thank you Sri Karthikeyan for answering the questions i posed – (as a child questioning his/her parents on aspects of hinduism and creation in today’s highly complex globalized world). Above sample questions and more similar questions when debated and answered by learned and visionaries may actually strengthen sanatana dharma in younger generation who will understand their roles better and answer critics, agnostics and atheists as well. Thanks for nice answers sri karthikeyan.

By the way i remember reading a book twenty years back titled like “Am i a hindu?” Written by a foreign-settled hindu indian a guide of sorts for foreign settled NRIs (written in question answer style as though his young child was asking these questions on hindu ways born in a different culture. Inspired by that i guess).

Good day to you.

This is in reply to a question raised by Sri. Gangadhar Sivaswamy on Varnasrama Dharma. There is nothing wrong in Varnasrama Dharma. The Varna concept is there in very ancient texts, prior to Gita. It can be seen in Purusha Sukta of Rgveda and in Brhadaranyaka upanishad. What we find in Gita in verses 4.13 and also in 18.42, 18.43 & 18.45 read with 3.35 & 18.47 is only an explanation/elucidation of the concept. In Gita Krshna represents Atman (verse 10.20). So, when he says ‘I’ it means Atman, if the context otherwise specifically requires to take a personal import. According to Upanishads, all beings and the entire universe are only manifestations of Atman. While so manifesting, Atman invokes the Maya (Prakrti) which is his own power for appearing variously. Prakrti is composed of three Gunas. As diversity is an essential requirement and feature of manifestation, every being has a unique dispensation of the three Gunas in varying ratios. This unique mix of Gunas in individuals determines the composition of his character, tastes, abilities, inclination to actions, etc. As his actions are determined by this composition, one’s Varna is determined by his actions done under the influence of Gunas. Krshna’s declarations in Gita are to be understood accordingly. Nowhere in the scriptures can we see a mention regarding classification of certain castes as Brahmin and others as Kshatriya, Vaisya or Sudra. Only caste is determined by birth, not Varna. No authority is there sanctioning the claim of certain castes to be Brahmins or Kshatriyas. The scriptural position is that very caste and every family can have persons belonging to all the four Varnas. Any arrogation of a particular Varna on the basis of one’s caste is simply unjustified; it amounts to a fraud.

Respected sir,

I do not much more about religion and Hindusim. But being born in Telugu Brahmin family, I always offer Lalita Shotram,Shiv Tandav Shotram,Vistnu Shotram,Gayatri mantram etc and other as far as I can in early in the morning.

May I know from your highness as to why the GOD has created this universe ?Why does he create so many creatures ? I am a part of Parmatma. But how am I responsible for any acts which are being executed by His orders. Please tell me.

Sir,

Today’s world is based on networking – social, professional, interests-based, locality-based, relatives/clan-based, community-based affiliations and the like. It is also a fact that today Dharma is a quarter of the ideal level of Satya Yuga and growing worse daily. It is highly likely then that a ‘Judas’ in each of these networks exist. Thus our friend’s friend or colleague’s colleague or neighbour’s acquaintance etc. may be involved in Adharmic behavior . The concept of a ‘Network Karma’ then arises due to hybrid people tied together only by a small criteria. How culpable (in terms of Karmic sin) are people today when /if we find such network member committing adharma ? What sin accrues to a Hindu for being a party to these activities? (Akin to Bheeshmacharya, Dronacharya, Karna in Mahabharata). Are there any scriptural guidelines people can apply today to absolve or stay from such

network karmic consequences? Thank you.

start vedapadasala and study veda mandras in order to get iswarya sasmruddi in our soceity

I kerala nambudiri belong to the lineage of shri sankaracharya I have my recitals of the vedas especially I am a rigvedist. As far as the Bhagavd geetha and the Mahabharatha and all our epics e should mind fold it thasn speak verbal Today such devotionasl practices are rare I think

THANK YOU

please send me emails on divine articles weekly

thanks

please gave it cobralore in indian folklore information